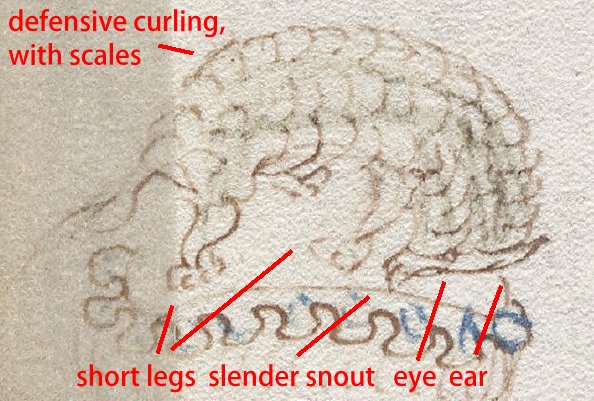

In the recent heated resurrection of the f80v “armadillo” identification controversy, many new and old issues arose surrounding it. But in all the discussions, it became apparent to me that not everyone was aware of the basis for my reasons I favor the armadillo identification.

I didn’t understand this at first, because I had long linked my page of armadillo pictures and engravings, beginning with my first post on the subject way back in 2009, “Dating an Armadillo”. And then, I linked that selection, again, in my very recent post, “ANYTHING but an Armadillo”. But apparently some have missed those links, and therefore misunderstood many of my arguments pro-armadillo. This post is to rectify this oversight. Below are my “pro-armadillo” arguments, both visual and contextual.

Point-by-Point Armadillo Comparison:

The f80v animal is, by most people, quickly recognized as an armadillo. Why? Quite simply, it seems there is enough of a recognizable set of features. The curling posture, a defensive feature of the animals, is well known. They have scales. The snouts are slender, as are the ears on some species. Also, the snout’s tip is often represented with high nostrils, which I think might account for the Voynich artist drawing a slightly “upturned” orientation to the tip of the snout. Also note the ears are pointy, and the legs are short. Look below at this 1551 illustration from Conrad Gesner’s Historiae Animalium:

I’m going to return to this image in the “context” section, below. But the form is very close, although the artist’s style is obviously different. Where the f80v animal deviates is in the very poor representation of a tail, as it is somewhat “wispy”, and not the definitive “rat like” tail of real and illustrated armadillos. And the f80v animal was drawn without bands. But note that the scales on both f80v and the Gesner version are both seemingly drawn oriented in the wrong direction: with the curved portion facing forward. This is not seen on real armadillos, but is an error of representation on several early engravings. Here is another version with this reverse-scaling:

That is from a 1633 book, and I apologize for losing the reference. I will try to find it. But meanwhile, note the scale orientation, the pointy ears, the upturned snout, the short legs, and the overall proportions. I think that from just these two images, it is clear that the f80v animal fits well with a 16th and 17th century understanding as to how these creatures should recognizably be illustrated (and therefore, also, how a forger of a 16th or 17th century armadillo illustration should represent one), and adding the oft-described defensive curling would be the “icing on the armadillo” (a lemon meringue, usually, I understand. Sorry). Here is another representation from the 16th century:

I had noted that this is from the 1593 book Aromatum, et Simplicium Aliquot Medicamentorum Apud Indos Nascentium, and also appears in the 1579 Simplicium medicamentorum ex Nouo Orbe delatorum, quorum in medicina, both by Nicolás Bautista Monardes. This version is different than the others on some points, such as scale representation, but still: In overall proportion, slender, upturned snout, short legs, and pointy ears, this animal is both very similar to the Voynich image, and also immediately recognizable as an armadillo. The next image is from a 1592 map of the New World, in Library and Archives Canada, item # NMC 8142:

He is a bit heftier than the f80v animal, with a thicker snout. And the scales now seem to be oriented properly… although it is unclear if bands are being represented. And the snout is not upturned at the tip. But still he has the general proportions expected and seen in others, and in the f80v animal. Further, perhaps, but still I think a good comparison. And in any case, I do not think this is the source of the f80v animal, because of those differences.

A point here, before I go much further: This post is about the “why of it”: the reasoning behind the armadillo. For all the previous decade plus arguments AGAINST the armadillo, see my post ANYTHING but an Armadillo. If you have a new objection over those, or a “pro” comment that has not occurred to me or others, I would be interested in hearing it below.

Expectations and practices of the Voynich Artist:

As I also pointed out in “ANYTHING but…”, objectors to an armadillo identity have claimed that the Voynich artist was either too good to draw it so badly, or conversely, so lacking in talent, that they would not have drawn and armadillo “this good”. That is, they would have either drawn it better, or worse, but not like we see it. Or, it is said, those are not scales, but fur, and not ears, but horns. But the thing is, we do not have to guess at these things: we have clear examples, elsewhere in the Voynich, as to how the artist drew various animal features, and the level of their talent.

So for the question of whether or not the f80v animal is representing scales? We have two scaled animals which compare closely to the f80v animal, showing the VMs artist meant “scales”:

So from these images alone, it is obvious the f80v animal has scales. If they meant “fur”, as many have suggested… such as seen on wolves, sheep, and other animals, then we also know how such a feature would have been drawn by the VMs artist:

And there are other examples in the Voynich, telling us how the artist represented these features, and more: How they drew ears, and horns, and eyes, and so on. And I cannot resist pointing out how Voynich himself treated these features, in his own drawing of a cat:

Similar to the above argument, also covered on my page “Anything but…”, it has been suggested that a person “of the time” (meaning, “15th century”) would or would not have drawn a thing this way, or that way. But however others might have so drawn the animal, in ANY time, is irrelevant, because we have the Voynich right in front of us, telling us exactly how they DID draw these things.

But what about the context?

And then, it has been claimed (“Anything but…”) that there would be NO reason for an armadillo to be in a forged Roger Bacon manuscript. That is true, there probably isn’t a reason for that. But the thing is, nobody I know of makes that claim, and I certainly don’t.

In my 1910 Voynich Theory, I hypothesize that the Voynich Manuscript was first created, about 1908 to 1910, as a Jakub Hořčický botanical. I think it was meant to look like it was written by the man claimed to have signed it, that is, “Jacobus Tepencz”, while he was chief botanist and physician for the Holy Roman Emperor Rudolf II.

And further, I believe the “primer”, or guide, for creation of this forgery, was the 1904 Henry Carrington Bolton work, Follies of Science at the Court of Rudolf II. This is a sometimes informative, but more often wildly inaccurate, although always colorful representation of the last years of the Court of the Emperor. It is a fun read, but far from a history lesson. It was a best seller in its time, and gave a great many people a skewed vision of life in the Court of Rudolf. And Wilfrid Voynich was no exception… he was a real fan of this very popular work, even telling others that he “knew it by heart”.

The list of comparisons to mentions in Follies, and those things noted in the Voynich, is tremendous, and a subject for another blog post in itself. But for the sake of this this post, I note Hořčický is one mention… as is his brother (???) “Christian”, and his “City Pharmacy”, with many New World… American… plants and medicines, which supposedly lined his shelves.

Voynich himself made private note of almost all the names in “Follies…”, listing them in order. It has been suggested to me that he did this to try and ascertain the origins of “his” Roger Bacon manuscript, that is, to discover “who” may have brought the VMs to the Court of Rudolf II. Possibly. But I posit, on the contrary, that Wilfrid’s list is highly suspicious, especially considering the above mentioned great number of similarities between the manuscript, and that “Follies…”. It is a “chicken/egg” problem, to be sure… but with those comparisons, I would say, “Follies” is more the chicken, and the Voynich ms., the egg. That is, I believe that Wilfrid Voynich did research the names in “Follies…”, but in order to include in his work many items he thought might appear in a manuscript herbal by the Court botanist.

Which brings us back to the Conrad Gesner armadillo, shown above. I had long noted that his armadillo engraving was probably the closest representation, in style and spirit, to the f80v animal. The pointy ears, the upturned snout, the look and orientation of the scales, and so on. I had thought this, in fact, before reading Follies of Science at the Court of Rudolf II. So one is welcome to dismiss this as just another of many troubling coincidences, but the very book this armadillo is from, is mentioned in Follies, on page 212:

“… the ‘German Pliny,’ Conrad Gesner, Professor of natural history at Zurich, whose ‘History of Animals,’ published in 1551, is the basis of all modern zoology…”

And there is a further supporting reason why an armadillo might appear in the Voynich, if a forgery meant to appear as a Rudolf Court production, as I contend: All the great minds of the early 17th century in Europe were quite fascinated by “all things New World”. Their “Kunstkammers”, or “Cabinets of Curiosities”, and much art representing those collections, there appear many New World artifacts, plants and animals, as they were very desirable. The armadillo is no exception. Here is the Musei Wormiani Historia of 1655:

Note the stuffed armadillo hanging up on the right. There is another armadillo on a shelf to the left, in this illustration of the Museo Cospiano. I found this and other images on this page of seven different collections, and I think there are at least four armadillos between them:

So there is a clear case to be made for the use of an armadillo in the Voynich, as explained in my own hypothesis. It has a very good reason to be there, as it would be completely appropriate… actually, expected… in a work meant to represent the Court of Rudolf II.

Mention must be made to the various New World Voynich theories, most of which do accept that the f80v animal is an armadillo, of course. I do think that a great many of the comparisons used in these theories, of plants, animals, and text, to New World sources, are actually correct. It is just that given all the other comparisons made, that deviate from “New World”, many of which are grossly anachronistic to the radiocarbon dating of the calf skin of the Voynich (comparisons up to 1909), I feel the New World content of the Voynich was by influence only, and penned in modern times.

This post does not go into the great many other reasons I feel are supportive of my 1910 Voynich Theory, nor does it claim the armadillo identity is the only pillar on which to base my theory. It is only one of a great number of observations, by me and others, which clearly show that that the Voynich (as a 15th century genuine manuscript) is rife with anomalies and anachronisms, which never get properly explained; nor are any appropriate, let alone better, substitutes offered, in any reasonable overall context.

But Rich, Wilfrid wasn’t a total idiot and his selling-point was that the manuscript was an autograph by Roger Bacon, who lived in England and in France (only), and a very long time before the armadillo ever appears in European sources.

For him to go out of his way to find and include the image of an armadillo would surely be self-defeating, as much as if I wanted to forge the image of a thirteenth century Byzantine icon and then set by her feet the image of an Australian kangaroo.

He’d have not only had to be a complete idiot to do a thing like that, but so would everyone else who saw and evaluated the manuscript. Keeper of manuscripts at Cambridge, Fr. Theodore Petersen, Erwin Panofsky and who knows how many others.

Besides, it looks to me as if the draughtsman has made very clear that those aren’t ears but bony projections more like horns. Whether meant for a real or an imaginary beast is difficult to say, but … armadillo, why? 🙂

please note – the above is addressed to Rich.

Hi Diane!

“Wilfrid wasn’t a total idiot and his selling-point was that the manuscript was an autograph by Roger Bacon, who lived in England and in France (only), and a very long time before the armadillo ever appears in European sources.”

For many reasons, in my opinion, this was not created AS a Roger Bacon work to begin with. As I wrote in this post, I believe the work was meant to “be” a botanical/pharma “by” Jacob Horcicky, who “signed” it. Besides an armadillo not being very “Bacon Like” (they taste like chicken, not pork… sorry again), neither is much else in the Voynich. And as we know, except for a very few “die hards”, the idea this had anything to do with Bacon didn’t last much past about 1922.

It is possible that the removed pages of the Voynich were taken out because they were too revealing as a circa-1612 work from the Court of Rudolf II, after Voynich decided to switch gears, and change the claimed authorship to Bacon. He may have done this because:

1) Perhaps he got negative feedback as a Horcicky, from Joseph Baer, Charles Singer, and maybe others. There is some evidence that Singer saw it at Baer’s, in Frankfort, as early as 1905 (I think maybe 1908 at the earliest).

2) Roger Bacon’s 700th anniversary of birth was coming up in 1914, and there was a public interest brewing in all things Bacon. Finding a “lost Bacon” would be far more valuable than an herbal/pharma from the Court of Rudolf, penned by an unknown.

So I believe that before the public unveiling, about 1911/12, of the Voynich, he chose to “make it a Bacon”, and pushed that, instead. Perhaps removing pages, and leaving only those earlier indications of the Court of Rudolf and the New World, such as the armadillo, the sunflower and pepper, and many other New World Plants… of 17th century optics, of the heraldry, of the swimming girdle, and so many of the other anachronistic items others have long noted… only those things he felt were not a dead giveaway. And they are not, are they? WE argue about them.

“He’d have not only had to be a complete idiot to do a thing like that…”

Why? It worked. If it is an armadillo that he left there, it is still fooling the vast majority of people. So I would say he was very clever, very prescient.

“…. but so would everyone else who saw and evaluated the manuscript. Keeper of manuscripts at Cambridge, Fr. Theodore Petersen, Erwin Panofsky and who knows how many others.”

But a great number of experts, pre-C14, believed this was a post-Columbian manuscript. So, no, they didn’t think this was an armadillo, to my knowledge, but it should not have bothered any of the number of early experts who thought this new enough to contain one.

“Besides, it looks to me as if the draughtsman has made very clear that those aren’t ears but bony projections more like horns.”

I appreciate you disagree those are ears. But for the reasons I give, in the OP, I think they are ears, and not horns, and would think as you do, the artist “made it clear”. We also know how the artist of the Voynich did draw horns, as we have examples, and it was not like that.

“Whether meant for a real or an imaginary beast is difficult to say, but … armadillo, why?”

For the reasons I gave in my OP, and in other posts. I respect you disagree with them, but I have answered that question: As a record of the botany, medicine, “sciences”, objects, interests and activities of the Court of Rudolf II, as seen and recorded by Horcicky, forged by Wilfrid, an armadillo would not only be plausible, but virtually expected in the manuscript. Every great collector in Europe had stuffed animals from the New World, and plants, and Native American collectibles.

Rich, Thanks, as ever, for your very civil reply and for taking the question soberly. Regards

The critter in question is not represented as isolated on the page. There is other drawing directly beneath it. Yet you do not mention this at all. What explanation do you have for the lower part of the illustration?

Hi Richard… I assume you mean the wobbly-edged “platform” the animal is on. Of course I don’t know what the specifically that is mean to be… but I’ve seen similar shapes used as “bases” for other artwork, sometimes sections of ground that a subject is standing on. And in the Voynich itself, there is a similarity to the “canopy” on the center building of the rosettes, so maybe, “sky”? Maybe “water”?

I don’t personally think it affects the armadillo speculation, nor any other, by anyone, real or fake.

In an attempt to put further context to the animal as armadillo, and more closely to the base you mention, and the page as a whole, I did look into the possible uses of the creature in medicine, cooking, and other, but have not found anything definitive that would explain it more specifically to the context of the page.

But unexplained, it does not seem to effect the animal, whatever animal, pro nor con. What do you think it is?

R. Sale: I was thinking that you may have meant the late Victorian porcelain Turkish spa fittings within which the royal nymph is posing, along with others similarly engaged on other parts of the page…I’m almost convinced that the mystery creature is in fact an artichoke that some helpful assistant has added legs and a head to during the artists cigarette break.

Hi Rich,

I understand the topic of this post to be the question *why* it would be reasonable for Voynich to include an armadillo in this ms, his supposed fake.

The answer seems to be that, by the early 17th century, armadillos were much in fashion, in documents about the Americas and in private collections of exotic items.

This second point is undoubtedly correct. They were.

However, every single illustration of the animal before (say) 1620, and every single illustration of a ‘Kunstkammer’ including one of them shows an animal with a completely straight back. This is clear from all the illustrations you present, and from others that one may find in literature or on the web. This is also logical, because they would not curl and could not roll up.

It is therefore very hard to explain why Voynich would have drawn an animal so different from the popular armadillo, namely curled up.

You start your blog post with a picture of the animal in the Voynich MS. You label his back as ‘defensive curling’. Well, curling can be seen, but why ‘defensive’? That certainly is a subjective interpretation, and seems to be an anticipation of the desired identification as an armadillo. The animal could also simply be sleeping or dead.

There is another very curled animal in the MS, namely on f79v lower right corner. I don’t think that this could qualify as an armadillo or that its curling could qualify as defensive.

Hi René: Thanks much for your input.

“However, every single illustration of the animal before (say) 1620, and every single illustration of a ‘Kunstkammer’ including one of them shows an animal with a completely straight back… …It is therefore very hard to explain why Voynich would have drawn an animal so different from the popular armadillo, namely curled up.”

Well first of all, I think that is applying a demand on the image correlation that goes far beyond what one sees in the Voynich illustrations in general. This effect is covered on my “Anything but an Armadillo” page, using your example that only the banded armadillo curls; the VMs armadillo has no bands, therefore it is not an armadillo (paraphrasing).

I think it entirely reasonable to expect that a person wanting to demonstrate, evoke, an armadillo would include the well-known curling feature as an additional aspect, whether or not the images that influenced the inclusion of it were showing it.

“You start your blog post with a picture of the animal in the Voynich MS. You label his back as ‘defensive curling’. Well, curling can be seen, but why ‘defensive’?”

It fits the overall context of the animal, as it already has most of the other features of an armadillo: Scales, proportions, snout, eyes, ears. So “yes”, once we have such an animal, this is an additional feature which fits with, and further identifies it: The well known defensive curling posture. Yes it is “subjective” as you say, as everything in the Voynich is, but I don’t consider it biased with anticipation of a desired identification.

But that is the nature of subjectivity, and I give you mine, here.

“The animal could also simply be sleeping or dead.”

Of course… it could be a scaled animal, with the proportions of an armadillo, with an armadillo-like head, snout, legs… and it could be dead, too. I was wondering, as I mentioned to Mr. Sale, if it was meant to look cooked.

“There is another very curled animal in the MS, namely on f79v lower right corner. I don’t think that this could qualify as an armadillo or that its curling could qualify as defensive.”

True, but then the rest of that animal has no armadillo-like features. To then propose that any other, non-armadillo looking animal curling, then cancels out the very armadillo-like animal’s curling, I think is not a plausible rejection of it.

But overall, I would say your points are of that same category, demanding that this identification be better than the alternatives suggested, and allowing the alternatives, or “no armadillo” at all, to be allowed, with less comparative quality, or none, and no context at all. I still contend that the armadillo provides all these things: point by point comparative features to one, and even, a bonus indication of the creature’s famous defensive behavior, all well within the technical and artistic abilities demonstrated by the Voynich artist.

What do you think it is, and in what context, and why? I don’t recall if you had a candidate, and I’m genuinely curious.

Being somewhat undecided as to what the creature on f80v might be or represent, I must say initially that I’m quite delighted that neither Rich or Rene ever refer to our VM animals as ‘critters’. I’d like to think that Rene’s f79v sketch is more likely to depict the typical butcher’s hook hung carcass, as characterised by the dead features, doubled up torso, with lumber loop line and bloody streaks on a hairless, (scaleless) body. Evidence of this is plainly represented on a number of typical 19th century British territorial crests, eg. NSW Australia with it’s hanging sheep portrayal on two quarters of it’s coat of arms..

Hi John! I see what you are saying, that the f79v animal could be a bloody, dead, hanging thing. But if not dead, also, I would not say there is any obvious similarity to the F80v animal, as René suggests… the back is a bit arched, as though lowering its head for grazing, or whatever.

In any case, for whatever reason the back is arched, yours included, I don’t see how it obviates the “defensive” nature of the pose of the otherwise already armadillo-like f80v.

If you have a link to those “British territorial crests”, that would be interesting to see. Thanks.

Rich.

Rich,

Perhaps you have touched on the essence of this entire discussion, that is, it’s a matter of interpretation. What you have called a “wobbly-edged platform” of little or no significance can be given an alternative interpretation when seen from a perspective based on the recovery of traditional terminology.

Specifically, the so-called ‘wobbly line’ fits the definition of a pattern found in the heraldic lines of division well before the VMs parchment dates. The definition is a regular meandering line in which the crests and troughs are bulbous. This is termed a nebuly line, with the origin of the word from the Latin, ‘nebula’, meaning a mist or cloud. In German the heraldic term is ‘gewolkt’ deriving from ‘Wolke’ which also denotes a cloud. And while this cloud-based interpretation certainly isn’t iron clad in all cases, it does open an alternative possibility. And it is also clear that there is a connection with the medieval use of the artistic technique known as a Wolkenband / cloud-band. In medieval art, cloud-bands function as cosmic boundaries. So, by extension, the nebuly line functions as the simplest version of a cloud-band or cosmic boundary. This usage clearly applies to the nebuly line found in the VMs cosmos – meaning that the creator of the VMs is aware of this cloud-based interpretation, even if some of us are not, though not to imply that every instance is a cosmic boundary.

So, if the nebuly line, cloud-based, cosmic boundary can be considered as a potential interpretation based on the recovery of traditional terminology, then there is a question that needs to be answered. What does an armadillo need with a cosmic boundary?

[That is a question I cannot answer.]

On the other hand, J K Peterson, in a recent blog regarding Agnus Dei, has posted several examples of a lamb inside a vesia piscis, which is another form of cosmic boundary. And in a few examples, the vesica piscis is represented with a cloud-band pattern.

One example is the “Apocalypse of S Jean” aka BNF Fr. 13096 which is dated to 1313, but known to have been in the library of Philip the Good, duke of Burgundy (d. 1467). Note the apparent droplets of blood falling outside the vesica piscis. Here we have a specific three-part construction: lamb / cosmic boundary / droplets. It looks to me as if the VMs ‘critter’ illustration is a parody of this same conceptual structure. And it seems to me that such an interpretation stands on much firmer footing, being an identification of a structure based on three very different parts in sequence, rather than just one part based solely on the interpretation of its appearance.

The ‘when’, ‘how’ and “why’ of it are certainly other matters altogether.

Well Rich, I don’t necessarily say the wobbly edge is of little or no significance, only that I don’t have a strong opinion of what it is, one, and two, don’t think that what it may be… if of any importance above decorative, including yours, would necessarily tell us what the animal is and is not.

As you know I don’t in any way reject your various heraldry and papist ideas and observations. I actually agree that many are plausible, and further encourage you to find an overriding context: Why they may be in the Voynich, who might have put them there, when, and why.

“What does an armadillo need with a cosmic boundary?

[That is a question I cannot answer.]”

Nor can I, if that is a “cosmic boundary”. But I’m not so sure that even if it is that, and what you think it is, that an armadillo would be out of the question. Maybe, maybe not. I know my critics would be screaming “Deal breaker! Agenda driven!”, and so on, but then I would reply, “Look at the rest of the damned book… we KNOW they are women, but then why in barrels and eaten by fish? It does not mean they are NOT women”.

But again, if you feel the context, “… J K Peterson, in a recent blog regarding Agnus Dei, has posted several examples of a lamb inside a vesia piscis, which is another form of cosmic boundary. And in a few examples, the vesica piscis is represented with a cloud-band pattern.”

… I honestly don’t argue with you, and it is a fair observation and opinion. I don’t personally think that proposed context is satisfying enough to see the creature as a lamb, but accept that it is a valid path for others, and would never attempt to discourage anyone from pursuing it.

Hello Rich,

Brooks Brothers logo from 1850 should work for you; Alternately Philip the good of France, created a society ‘Order of the Golden Fleece’ in 1430 and you can get many variations of his own hanging lamb motif on it’s coat of arms off the main board. Same with NSW and other state crests as stated.

Thanks, John, I’ll check it out.

Rich – we don’t know they *are* women, only that the majority of the forms are depicted as females. Women have female form of course – but the same is given to non-living beings such as deities, or entirely allegorical figures such as Justice. Sometimes the form male of female form for a thing reflects only the gender given it in a specific language, as Justice in French (for example) takes the female gender: ‘La Justice’.

As regards that wavy line – it has a very long history in the Mediterranean traditions and consistently marks that indefinite line between the proper demesne of human kind – the earth – and that alien to human life, as the sea-strand or the higher skies. The same convention placed within the world of humans the clouds, winds, sun and moon, so the convention of describing it as the ‘cloud band’ isn’t exactly accurate, but near enough.

Hi Diane! Yes good point about the “women forms”. And the wavy lines…

Thanks for the input. Rich.

Speaking of ” women forms “. Try miss legs’n ass standing under the umbrella tree in f100r. Great body though can’t see her head but very art neuvo-ish; not at all like the decidedly tasteless medieval copy nymph forms elswhere on VM.

I am supposing you mean this illustration:

https://www.jasondavies.com/voynich/#f100r/0.816/0.295/4.23

It could be a coincidence, and that is what many will say… but I do have to say I see your point there.

In any case, the overall style of the women forms in the VMs, are, to me, what you say… bad copies of medieval… and Renaissance, forms. I looked a lot at late 19th and early 20th century cartoon art, too… because there is something very “cartoonish” about the forms to me. They are loose, and not serious, and remind me much of the Katzenjammer Kids:

The Yellow Kid: https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/f/f1/At_the_Circus_in_Hogan's_Alley.gif

Little Nemo:

In any case, the forms look little like anything authentic to me, not to mention that the style does not match any medieval one even remotely. I would go as far as to say that not only was this forged, but it was not even, in the beginning, a serious attempt to fool anyone. It may have been a whimsical, inside joke, or like that, at first… that took on a life of its own. I think it is that bad.

I’m not quite sure what we can expect to take fromTom O’neil’s Wilfrid Voynich Morse code based transliterations of those Italian glyphs with English dialectic flavoring, so to speak. My own interest was in Tom’s clever use of the Sessa coat-of-arms Tom & Jerry theme to explain how he was first able to identify Wilfred’s name in the heraldic outline and it’s apparent message in Morse Code.. My personal view has for some time been that the cat’s somewhat unusual shade pattern may have included a security identifyer code within, but we can get to that stuff later.

There is no doubt that Voynich was quite conversant with a number of common languages, typically Italian which he needed for buying books at the Mondragon Palace around 1900 or thereabouts; Plus Spanish for communicating intelligence with Mexicans like the other Mondragone in 1915 whilst working for the British Admiralty and secretly with the Americans from NY.. Of course his use and knowledge of Morse enabled him to have secure telegraphic links to anywhere in the Americas and to some extent with his old spy mates ie. Sidney Reilly in Brazil or others on the Continent…

Pingback: The Sources for the Voynich Forgery |

Pingback: Sources for the Voynich Forgery |

Pingback: I Do “Listen to the Experts”. Do YOU? |