I was prompted to write this post after being chastised some months back, as I often and similarly am, for my non-mainstream Voynich Manuscript theories. The comment was by Koen Gheuens under Elmar Vogt’s excellent December 2023 blog post, “Time for an Inventory“:

“… Also, Rich, if you feel constrained by the opinion currently held by most, if not all, professional researchers (that the manuscript is genuinely medieval), then I don’t think the problem lies with them.”

As I said, Koen is far from alone. As I’ve traveled through my various theories on the Voynich, if not more-so as I’ve come to rest on my current hypothesis, I have been told, over and over, that my “problem” is that I simply refuse to “listen to the experts”. And that, if I only did listen to them, I would give up my crazy ideas, and accept that the Voynich is a genuine 15th century manuscript.

But is it me that does not listen, or is it the critics of my theories?

First of all, while Koen accurately identifies my very skeptical nature in his comment, have to disagree on a couple of points: First, I don’t actually “feel constrained” by any particular belief or opinion, expert or not. And also, I don’t consider that my doing this a “problem”, but actually an asset. Skepticism is one of the driving forces of science, or the investigation of any mystery or problem. Without skepticism we stagnate. Any worthwhile advance in any field is the result of questioning some previous status quo, and not by blindly accepting it.

I then outlined, in my comments, what I consider the many reasons I feel the way I do about questioning opinions. But after listing my reasons one should always, at least, question expert opinion, I came to the realization that it is, ironically, me who has and does accept most expert opinion. In fact, I actually reject far less of it than my critics!

But how can that be? Don’t I feel the Voynich is a modern forgery, circa 1910, while few, if any, experts agree with that assessment? Wouldn’t it be, then, my critics who are the ones who “listens” to them, and me, who “ignores”? No, not by a long shot. Let me explain:

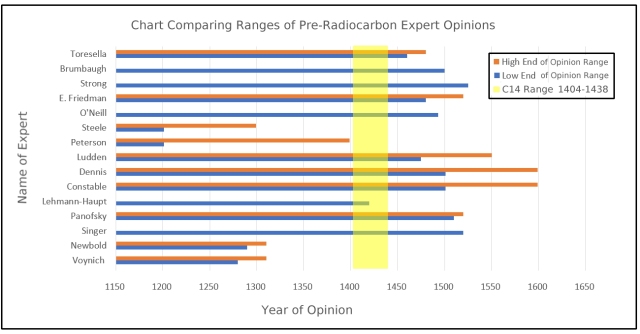

First of all, let’s look at the converse: How most of my theory’s critics are the ones who have actually have dismissed the vast bulk of expert opinions on the Voynich. I’ll start with those opinions which came before the revelation of the radiocarbon dating results in 2010. I have posted the tally of these pre-C14 opinions several times over the years, and recently summarized them in a chart on my blog post, “No Expert ‘Got it Right’“:

Pre-C14 Expert Dating

As I also point out in my 2015 post, “Modern Voynich Myths”, soon after the C14 results were revealed, it was said that the “experts got it (the dating) wrong”. But within mere weeks, the list of of these experts was rapidly winnowed down, until the new claim was, “The experts got it right!“. Why? Well, it seems, the C14 dating, and the erroneous and insupportable contention that ink was always applied soon after preparation, were combined into a sort a supposedly unassailable time of origin for the whole damned thing.

Almost immediately, any name on the expert list that was deemed “too far away” from the determined 1404-1438 results was simply crossed off the list. After this purge, only two experts remained: Lehmann-Haupt, a book cataloger, and Erwin Panofsky, an eminent art historian and scholar of iconography. But wait- why isn’t Panofsky, often cited as one of those “right” experts on the Voynich, on my list? Did I cross him off because of my own biases? No. It was simply because he changed his mind. After his initial, brief two hour examination of the manuscript, he did place the date close to the eventual C14 dating. But later, on further thought, he amended his opinion to a hundred years later! I prefer to take his (expert) word on it, and trust his correction.

So then, anyone who believes the Voynich is genuine, and circa-1420, must reject all those 14 pre-C14 experts who said the manuscript was anything BUT 1420. But I do not reject them. I actually agree with virtually all their observations. The thing to realize here is- the reason my seemingly hypocritical belief that the Voynich is a circa 1910 forgery, while the experts did not- is simply because these opinions were not about, nor considering, whether or not the Voynich is a forgery. These experts were looking at the style and content, and then giving their expert opinions as to when and where that style and content most likely originated from. These were not forgery experts, they were art historians, linguists, scholars of the history of the herbal tradition, of iconography, cipher, codeology, palaeography, and so on.

And it became clear to me, long ago, that the most logical explanation for all that the experts observed in the Voynich- which was from many different sources, eras and geography- is because this is a modern forgery. No real work of literature nor art has such a conglomeration of such a wide spread of sources, places and times, unless it was made in modern times. And if made in modern times, it is fake.

I also believe this “conundrum of expert opinions” has also been painfully apparent to those who hold onto the theory that the Voynich is genuine, and old, and that this is exactly the reason they “Don’t listen to these experts“. In order to continue to contend that the Voynich is genuine, and 1420, they must erase this vast corpus of brilliant and experienced expert observation which tell us otherwise.

As an aside, I have often imagined a sit-down debate between the esteemed, prolific and accomplished Charles Singer, with any modern adherent to the 1420 Genuine Herbal Cipher Paradigm. I would love to hear how they patiently explain to Singer why he is wrong, and why the Voynich has no Paracelcian content, and how it was actually created over a hundred years before he believed it was. I’ll make the popcorn. But the same goes for any on the list of experts who are all now said to be wrong. I say, rather than just eliminate their presence, actually explain why they were wrong. Argue with them, don’t simply ignore them. And no, simply saying, “Because C14” does not, should not, suffice. Especially since the dating only tells us when the calf was slaughtered, and not at all when the ink was laid down on their remains. All the content observed, by all these experts, in all their proposed eras, CAN be on that calfskin, if a modern forgery. So explain why they are all wrong, and don’t just tell them to go away.

But the same goes for any on the list of experts who are all now said to be wrong. I say, rather than just eliminate their presence, actually explain why they were wrong. Argue with them, don’t simply ignore them. And no, simply saying, “Because C14” does not, should not, suffice. Especially since the dating only tells us when the calf was slaughtered, and not at all when the ink was laid down on their remains. All the content observed, by all these experts, in all their proposed eras, CAN be on that calfskin, if a modern forgery. So explain why they are all wrong, and don’t just tell them to go away.

But then, you ask, what about the post-C14 expert opinion? Why don’t I listen to them? Well, again, I do listen to a great deal of it. But I will point out that there is more than a minor distinction between pre-C14 and post-C14 opinion: The probability that anyone with knowledge of the C14 results is taking it into account when opining on the date of the Voynich’s origin cannot be ignored. And I believe this supposition is supported, since the majority of experts didn’t think the Voynich was circa 1420 before C14, and yet, most afterwards, do. That this alone is evidence of such a bias to the radiocarbon results. I mean, it is too much of a coincidence for me that dating opinions were all over the map the day before the release of the C14 results, and then, everyone had a sudden “come to Jesus moment” exactly after the revelation.

Everyone knows where the water is after the well is dug.

In fact I’ve only heard from one modern expert, a paleographer, who made the claim to me that it was “clear as day” the Voynich was early 15th century, and that she knew this long before the C14. However- and forgive my skepticism- I have yet to find her opinion in writing to back it up. I’m not saying it was not possible this is the case, I only know it is, if it exists, a rare opinion (and would have been, in fact, counter to the prevailing expert opinions- if they believed this, they were a maverick). And because I do, actually, believe we should value and use expert opinion, this rarity alone is meaningful to me. It tells us something, and we should listen to what the experts didn’t tell us, too.

As for post-C14 expert opinion which now disagrees that the ink was applied soon after calficide, there are actually many examples. For instance, many renowned experts believe the Voynich Manuscript is post-Columbian, and therefore far newer than the 1404-1438 radiocarbon range. Among these are (the late) Arthur O. Tucker and Jules Janick, authors of Unraveling the Voynich Codex and Flora of the Voynich Codex: An Exploration of Aztec Plants. They also wrote, Unraveling the Voynich Codex, a book I highly recommend. They make many plant and animal comparisons which could only appear in a post-Colombian manuscript. They also make credible connections between the Voynich script and Native American Nahuatl, an idea first posited by John and Jim Comegys, years earlier. They also, independently to me, noted the use of the (possible) “Calderon”, a type of New World paragraph marker, to the “Bird Glyph” on f1r.

And Gordon Rugg has suggested a dating post-1550, possibly as a ruse by John Dee and Edward Kelly to fool Emperor Rudolf II. His work describing a possible construction method using a “Cardan-like” grille system is the the only peer reviewed work on the Manuscript, and again implies a date far later than 1420.

I also listen to these experts, and many like them. I do believe there are probably New World plants and animals in the Voynich, and possible influences from Nahuatl script, maybe even other attempts at transcribing Native American spoken languages. And so much more.

Furthermore, there is an important point to consider: Each and every one of all these experts must be wrong, or, at least, each and every one of their opinions on comparisons must be incorrect, in order for the Voynich to be genuine and old. If even one of them is correct– if the sunflower and the Nahuatl, and Harriot’s Algonquin, if the f80v animal is not an armadillo… and a hundred other comparisons are all wrong, but the calderon is alone correct, then it must be post-Columbian. And so on for all my own, chronologically later optical comparisons, and all the similar iconography in other works, noted by me and many others (whether or not they believed the Voynich to be modern): They can, save one, be incorrect- but then if, alone, the f69r “wheel” is a diatom, then this has to be a modern fake.

Genuine needs to reject all evidence to the contrary; fake needs only one comparison to remain.

But what about the actual feedback from the modern experts? Aren’t I rejecting, ignoring, that expert opinion which points to the Voynich was created in the early 15th century? Well, for one thing, as I wrote, I would treat with skepticism any post-C14 opinion as being possibly biased by C14, for the reasons I’ve outlined above. But let’s assume, for the sake of argument, that no post C14 observations are so biased. What then happens, when one reads, critically, the actual statements of the experienced, intelligent, and honest observations the modern experts have related after examining the Voynich, I would posit that those observations actually show a suspicious raft of damning anomalies and anachronisms. This can probably be best represented by Yale’s own 2016 publication on the manuscript, which is often cited to rebut my own theories, and those of others who feel the Voynich is something other than what the authorities and institutions try to tell us it is.

I was compelled to make such a critical examination of the Yale work when my theory was challenged in René Zandbergen’s blog post, “Why the Voynich is Not a Modern Fake“. While that post does attempt to refute, really, any modern forgery hypothesis, and does not mention me by name, it does include many references to my original discoveries, observations, and opinions. Which is fine of course, but understandably demands a refutation, as I think the included contentions are incorrect.

Many of the opinions expressed by René in that post are relating to information collected and reported in the Yale book. But when I did read that book, rather than supporting “nofake”, it became obvious to me that what was actually being described were the great many unexplained problems with the Voynich. I point this out in my response to René’s post, “Rebuttal to NoFake“. I show just how the Yale book actually reports many anachronisms and anomalies in the binding, design, and construction of the manuscript. And many of them are dismissed with the suggestions that further testing is needed to explain them. Others are “explained” with what I consider implausible, and even provably incorrect grounds, when I think they are better and more simply explained by a modern, i.e., forged, origin.

So I listen to those experts, too. I do not reject their observations, only some of the reasoning behind their conclusions.

“The quantity and size of the foldouts in the Voynich Manuscript are very unusual for the time period; it is rare to find so many large pieces of parchment folded into a single textblock, and this seems to indicate authenticity: In the twentieth century it would be quite difficult to find this many large sheets of genuine medieval parchment in order to produce a forgery.”- Yale, 2016

“No, it wouldn’t be ‘difficult’ at all. It’s called a ‘folio’“- Rich SantaColoma, 2008- present

One other expert report which is often cited, and should be considered: The 2009 McCrone ink analysis. This is often used as expert evidence that the Voynich is old and genuine. But the report actually never explicitly states either, and in fact describes several troubling and unexplained features of the inks. Among these are unidentified binder in the ink (not in their “library”), “unusual” copper and zinc, a “titanium compound”, and the controversial discovery that the (previously, supposedly newer and differently authored) f116v leaf marginalia was actually written in the same ink as the main text! I have long listened, carefully, to the expert opinions of McCrone. I read and consider all of it, but you will not hear a satisfactory explanation, if any, to those anomalous points found within it.

In conclusion, I think it is clear that it is actually I, myself, who “listens to the experts”, while it is actually the proponents of the “1420 Genuine European Cipher Herbal Paradigm” who do not. Who cannot, in fact. Because what the experts tell everyone is that we have a real problem here: It is a problem composed of many facets, contradictions, many conundrums, all of which do not come close to fitting within any 15th century genuine context, and which are therefore simply and most logically explained by the Voynich Manuscript being a modern fake.

Rich – I also think well of Charles Singer – in his own field – but that field was the history of technology. Some people are just lacking any natural aptitude for such things as reading images or having a feel for provenance. I’m sorry to say that he was one. His ‘ideas’ and ‘feelings’ about the Vms are just speculation and the really telling point, I think, is that he did not (unless I’ve missed it) see anything technological – such as guns, cannons, or machines – anywhere in the Vms. What drives me nearly to despair about Voynich studies is that people with theories rely so heavily on asserting this-or-that about the drawings, yet show not the slightest sign of having tried to learn how specialists approach the work of identifying the time, region and cultural context proper to a given drawing. As noted in the conversation at Elmar’s blog, everything seemed to start dying around 2012.. but that’s also when people were turning from manuscript-research to nothing but theory-research and fights about whose theory was better, and people began defending theories by attacks on character. Actually it started from the time Stolfi produced the results of his statistical analysis of Voynichese… escalated when I agreed the manuscript made in the early 15thC but was unable to agree that first composition of the content occurred then, or in Latin Europe… and has continued ever since.

Hi Diane! Thanks for the comments. As for this, though,

“I also think well of Charles Singer – in his own field – but that field was the history of technology.”

That is but one of his fields. While Charles Singer “… was a British historian of science, technology, and medicine”, and he wrote “The History of Technology”, he was also an expert on the “Herbal Tradition”, as it related to medicine… the subject of most herbals.

He studied, lectured, and wrote on the history of medicinal/herbal/botanicals. I have and read a copy of his 1928 “From Magic to Science: Essays on the Scientific Twilight”. Yes he does cover the subjects of science and technology in it ( a water clock, plan of a hospital, a Roman crane, etc.), but also botany, medicine, magic, astrology. He has chapters titled, “Early English Magic and Medicine”, “Early Herbals”, and “The Visions of of Hildegard of Bingen”, and so on.

The point is, I would say that he was “well equipped” to cast a respectable expert opinion on the Voynich, which seemingly does cover many of those topics he was so well versed in, and which he studied, lectured and wrote about.

Of course, though, what you describe is what happened to all the experts on the list. Long ago I was told that this expert, and then that expert on the list were “not the right expert” to judge the Voynich at all. Always though, the inclusion or exclusion of the chosen expert followed the particular hypotheses of the person tailoring the list, and/or to remove those with opinions which didn’t match the C14 well enough.

And that is the exact point of my blog post you are commenting on. I don’t actually disagree with you, though, because it is of course all subjective. Any one of the experts out there may or may not seem correct for any particular person’s theory as to what the Voynich may be, or not be. So, for instance, Singer may be totally inappropriate a witness to your views on the Voynich. I get that, and never meant to imply that anyone SHOULD accept all the experts on that early list.

My point was that I do accept them all, while constantly being told I do not, by the very people who do not accept them to begin with. Oh, the irony!

Thanks Rich for the reply. It’s a rare pleasure to have a genuine give-and-take conversation with someone else working on this manuscript. In fact, Singer served as editor for a History of Technology in several volumes. He didn’t actually write it himself.

He was not a specialist in palaeography or codicology – the essential elements for dating a particular manuscript’s manufacture.

He could write accounts of medieval herbal manuscripts, but what was needed was rather the skill-set, natural talent and comprehensive learning of a Panofsky. Not that Panofsky was perfect. He was really only interested in prominent individual artists and he fell into the general habit of attributing the manuscript’s divergence from Latin customs to the idiosyncrasies of a single author. But in those days, history was still all about “important man does important things impacting the history of western Europe” so he must be forgiven for not transcending the attitudes of his own time.

Thank you, Diane.

Rich – you say “No real work of literature nor art has such a conglomeration of such a wide spread of sources, places and times, unless it was made in modern times”.

That’s not so. Even if you limit yourself to medieval western Europe, there are manuscript compilations or miscellanies … say, about matters mathematical… in which we see material gained from ancient Greece, from ancient Sicily, from earlier medieval north Africa, from later medieval Spain, from Baghdad and from England. This is less evident in any drawings – as diagrams – because e.g. geometry’s diagrams look much the same no matter where they come from or where made. You can also find manuscripts in which the text is a thousand years older – and composed in a different continent – from the illustrations – I’m thinking here of a fifteenth-century illustrated copy of Augustine’s “City of God.” What is unusual about the compilation we have as Beinecke MS 408 is not to only that its drawings speak to a number of different cultural origins and periods, but that the drawings have been so faithfully copied that it is possible to recognise, to date and to place the original(s) first formation, and to distinguish medieval European additions or adjustments.

Just btw – on the subject of experts (an I prefer to speak of specialists), each is a specialist only in his own field; not all of the ‘experts’ in your graph deserve their opinion to be given equal weight. I’ve seen no evidence that Singer ever laid eyes on the manuscript, for example and it wasn’t Singer but Dorothea who did so much of the hands-on work with medieval European manuscripts.

Thank you for your points about manuscript compilations, and I stand corrected.

Yes on Dorothea… I had her my initial response, and edited it down. Per Wikipedia, “… Dorothea Waley Cohen, distinguished in her own right as an historian of the Medieval period. She provided valuable assistance in his publications for the remainder of his life.”

Charles Singer may not have seen the Voynich in person… but he thought he had, for some time. Whether or not this was correct, he did think he saw it, as early as 1905… but probably more like 1910… when he visited the bookstore of Joseph Baer: https://proto57.wordpress.com/2012/08/19/the-voynich-in-1905/

Now I did amend that post to say he didn’t see it… the “update” at the top, with Singer’s letter of apology. But in retrospect, I still wonder. It seems that he knew Ethel was upset about his claims, and being a gentleman perhaps he simply withdrew them. Because of course the hoopla at his having seen the Voynich before 1912 would imply that Wilfrid was a liar. Fake or not, it would mean he actually got it at least a dozen years earlier than he claimed.

In any case, he was familiar with the Voynich… if not having seen it directly… I’m on the fence with that… then through the photostats (I think, I’ll have to check), or other, published, images.

But this is a good point, actually: He certainly opined on the Voynich… so if he wasn’t granted access to the original, nor to the film copies, by Ethel and Anne, then where did he see it? From what source did he form his opinions? He was certainly no fraud, whatever his credentials. I think, then, it adds weight to his having actually seen it, in person.

By the way, I had ordered copies of several of his lectures, from one of the Singer archives. I’ve been trying to track down his notes about “whatever” manuscript he was lecturing about, which he thought was the Voynich. I’ve not found said reference so far, but I intend to continue. Also, there is a vague reference to a manuscript in “From Magic…” which I think could be referring to the Voynich. But it is far too obscure to say either way.

One last comment – your quote from the Yale volume –

““The quantity and size of the foldouts in the Voynich Manuscript are very unusual for the time period; it is rare to find so many large pieces of parchment folded into a single textblock.”

I find statements like that a little irritating. They neither say it’s unprecedented for a Latin medieval manuscript, nor provide examples of why it’s only described as “very unusual”. If there are any other examples – why don’t they give details?

Hi Diane: I find it irritating, too, and also very “telling”. It is, to me, a perfect microcosm of a problem that is fundamental and pervasive in this whole field: That this is all “science done backwards”. The evidence that is found is adjusted to their preconception of what they believe the Voynich is or should be, rather than the evidence being properly used to solve the problem.

This comment actually lays this bare, it is out in the open. It is obvious here, it “gives away the game”. But I see it in a hundred different ways, just not as obviously and openly done.

To the credit of whomever wrote that, they were at least upfront enough to relate the “unusual” nature of the foldouts (for the era they believe the Voynich was created in). And I see the second part, denying the possibility of it being forged, as a sort of almost subconscious admission that that is EXACTLY what the unusual nature of the foldouts is implying! It is exactly the case of thousands of other such observations, large and small, which tell the honest observer “there is something wrong with my beliefs”, and then, they retreat immediately back into their own preconceptions.

Anyway, about the rarity of such foldouts: It is actually not as much “very unusual”, as totally non-existent, for the C14 range. I’ve focused on this feature quite a bit, over the years. I’ve written to experts, read up on it, searched for examples like this. The only case I could find is a sort of “accordion” prayer book, carried by monks on their belts for portability and access. Such books are a long zig-zag of folded leaves. VERY different from the foldouts in seen in the Voynich.

That sort of foldout… used in atlases, or any book in which an illustration larger or longer than the normal page size is desired, which is presumably why they are used in the Voynich…. does not appear (if memory serves me, I would have to revisit this to be sure) until the late 17th, or even, the mid 18th centuries. I am not sure… ready to be corrected… that it even appears in any parchment manuscript.

But here is another thing about the Yale statement: The writer of that logically tortured paragraph is either missing, or ignoring, a major implication here: Those foldout pages belie the possible use of full sized folios! The Voynich is, of course, quarto size. The rosettes page as a whole, and the width of the other horizontal foldouts, “just happen” to fit the dimensions of a full sized folio?

No, rather than thinking the creator had to run around and dig up bigger leaves to make them, I think it is much more probable that the whole Voynich is cut down from a stash of folio size sheets. And then, they simple left some big, and long.

Other evidence of this is Pelling’s observation that various scars and repairs align across different leaves. And Dana Scott’s observation that there are some lighter, straight cut edges on many of the leaves… as though they were cut from larger stock.

Whatever the Voynich is, or turns out to be, I think that this area should be investigated. In fact it is solvable… because one could simply catalog all the light, cut edges, and the location and orientation of the Pelling scars, and then see if it would be possible to virtually recreate the original full folios the leaves of the quarto Voynich were cut from.

But it won’t be done. The preconception that this is a 1420 Genuine European Cipher… the Driving Paradigm… filters all investigation, and also all opinion, as we see, time and time again. True investigation stops at the exit door of that Paradigm, and will not be allowed to go any further. Any opinion, or result, that counters that view will be ignored, or dismissed on faulty grounds, or spun into a “conclusion” that is not only not warranted, but actually, in many cases, is the opposite of what is really being implied by it. Like this “foldout” statement, a clear and irrefutable example of this.

For that reason, I’m very glad it made it to press.

One theory for the presence of those foldouts: https://proto57.wordpress.com/2015/08/04/the-three-quire-theory/

Hi Rich- I’m glad to see you are posting again, and it is fortuitous that the foldouts came up in this most recent discussion, because I’ve been sitting on a hunch that I don’t know what to do with. It is a real Hail Mary, but I think we have gotten to that point in the game.

Have you ever heard of the Wellcome St. Cyprian manuscript? It is available as “Cyprianus, M.L.” at the wellcomecollection.org. I recently came across it and it struck the same chord in me that the Voynich did when I stumbled across that insoluble mystery so many years ago. It has the same “too-fantastical-to-be-true” movie-prop quality that makes the Voynich so sensational and, to my mind, so suspect. Even if there is no connection to the Voynich, it is still worth a look. The illustrations have a haunting quality and I wouldn’t be surprised if it did become a movie prop someday (in the Exorcist franchise, perhaps).

It was sold at Sotheby’s in London in 1912. That is the only provenance provided by the website. Who sold it and where it came from is notably missing, but I think the date and location put it within Voynich’s area of operation at that time, although I could be wrong on that.

The two works have very little in common, but enough to be intriguing:

-foldout with circular astrological-type charts (based on your statement above this may be one of the earliest examples, and maybe the only other one on calfskin)-

-contains cypher

-no clear provenance beyond the current owner (or maybe deliberately withheld provenance)

-calfskin

-apparent anachronisms (per Wellcome: “the date is given as 1717… but the script seems to date to the late 18th century”)

-mystical subject matter

What they don’t have in common:

-artwork is better in the Wellcome Cyprian (it is also much shorter)

-parts written in cypher are in a known code

-not nearly as old

-mystical subject matter is of a very different type (religious, magical)

It’s pretty thin, but maybe this grimoire was a test balloon for something much bigger, more mystical, and more enigmatic. You’ve said that Voynich had been linked to some possible forgeries in his career as a rare book seller. I guess my thought is, if this manuscript, with its foldout, cypher, and mystical content, could be linked to Voynich it could strengthen the Modern Forgery hypothesis. Maybe an associate of Voynich or Voynich himself was involved in the sale. There is also a distinctive gilt stamped, brass clasped cover, that to my eyes looks ecclesiastical, that was possibly removed from another book and could be a clue to its origin.

Not sure if anything can be done with this hunch, but I figured if anyone can do something with it, it would be you.

Hi, Dunstan: Thank you for the comments.

I had a chance to check out the Wellcome St. Cyprian manuscript, and I agree it is a parallel to the Voynich in many ways. Whether or not there is any connection is hard to say… unfortunately the description given is too lacking in details. Frustratingly so.

I would love… you would, too, I imagine, to see a more complete provenance for this manuscript: Where did it come from? What was the chain of ownership? And so on.

Testing would be nice, too: The calfskin, the inks, and so on. The problem is usually that the collections both don’t want to pay for this (understandable), and that they have no reason to do it. At best it is what they think it is, at worst it is bogus. It is lose/lose to do testing.

Maybe we can ask the Wellcome if they have better provenance for this, or that it can be found with an internet search. I’ll try to do that in the next couple of days, if I can remember. I’m swamped right now, with other tasks, and working on my car… which looks like the Scarcrow in the Wizard of Oz after the flying monkeys got done with him.

Thanks again, I love this stuff… and great find! Rich.

Rich,

With your encouragement, I did some (over)due diligence on my wild hunch about the Wellcome St.Cyprian and found the definitive text on the Clavis Inferni, as it is called, written by the same two researchers who “rediscovered” the manuscript in the Wellcomearchives in 2004. Surprisingly, it is available in full at the internet archive: https://archive.org/details/ClavisInferniTheGrimoireOfCyprian

These researchers do an incredible job connecting the text and images in the Clavis Inferni to previous grimoires and other sources from which they were drawn, most notably Pietro d’Abano’sHeptameron and the “Faustbook” Magia naturalis et innaturalis, which i think were both widely available in print by the late 19th century.

With regards to provenance, they claim to have been totally unsuccessful in finding any, and although they don’t come right out and say it, they suggest that the book is possibly a hoax (or at least more of a hoax than the other demon summoning grimoires) in so much as the author was likely attempting to give it more “aged provenance”. This all stems from the grossly incorrect and possibly manipulated Roman numerals on the title page.

Although the foldout and the location and timing of the sale suggests a possible link to Voynich, the botched Roman numerals seem to argue against it. It would still be interesting to find out what the Wellcome Museum and Sotheby’s records have to say about the purchase. Although, it does seem like the museum may have buried the thing out of embarrassment.

And now I’ll move on to my latest bout of palaeographic apophenia…

Have you ever come across the The Long Desired Fulfilled Knowledge of Occult Alphabets, or, if that isn’t spicy enough for your taste, The Book of Desire of the Maddened Lover for the Knowledge of Secret Scripts?

The manuscript was discovered in Egypt in 1850 by Joseph VonHammer-Purgstall who seems to have been a legitimate scholar. It is attributed to Ibn Wahshiyya, a real 9th century Nabaetean scholar, although this attribution, as is typical with magical texts, is widely regarded as spurious.

The book, which is dated to the 9th or 10th century, consists of hundreds of pages of “magical alphabets” alongside their supposed Arabic equivalents. The scholarly consensus is that the majority of the 89 “alphabets” in the book are verisimilitudinous creations of the author. Among the minority of real characters that are“translated” into Arabic letters are a selection of Egyptian hieroglyphics. Based on this, the author of the book has been occasionally credited as the first scholar to suggest that hieroglyphics were phonetic and not purely symbolic, which is an honor that is usually bestowed on the Jesuit scholar Athanasius Kircher some 600 years later. Although Kircher was aware of Ibn Wahshiyya and mentioned his work in his writings, I have seen no evidence that he saw this particular misattributed text, and considering that all the alphabets and symbols in the Occult Alphabets are given Arabic phonetic equivalents, even the author’s bogus ones, the claim that pseudo-Ibn Wahshiyya recognized the phonetic value of hieroglyphics seems questionable to me.

The provenance of the book is attested, rather vaguely, in a 10thcentury Arabic manuscript that describes “a transcription of the alphabets with which the books on the Art and magic are written” and says that Ibn Wahshiyya wrote about these alphabets. From what I can gather, it is this single reference that has convinced a majority of scholars that the manuscript is an authentic 1000-year-old hermetic text.

There is a minority opinion, however; that the text is a late-Renaissance forgery using Kircher’s own works on language(Prodromus Coptus is specifically mentioned) as source material. At the core of this theory is the observation that Kircher’s 16th century printed works and the 9th century Arabic manuscript both focus in on an obscure pseudo-Egyptian symbol that is known from only one source – an artifact discovered after the 1527 Sack of Rome known as the Bembine Tablet.

When Kircher was studying the inscription on this tablet in the 16thcentury it was believed to be an authentic ancient Egyptian artifact. However, post-Rosetta Stone scholars have determined that the religious imagery and hieroglyphic text on the tablet are nonsense, and it is now believed to be a 1st century CE Roman work done in the style of ancient Egypt. Even those who believe the Occult Alphabets manuscript to be genuine have trouble explaining how two books written so far apart in time and space could focus in on the same obscure, singular image and they have gone even so far as to suggest that it may be a fraudulent Renaissance addition to an otherwise authentic 9th century manuscript.

In summary, the Occult Alphabets is a manuscript that:

• contains page-after-page of fictitious but believable characters

• most scholars accept as authentic because it matches a vague reference in another text

• has been called into question due to a single image that is unique and identifiable

• can be linked to the work of Athanasius Kircher

Regardless of whether the manuscript is real or a forgery, these details are very familiar. I don’t know when this controversy arose,or if Voynich was aware of it, but the whole episode could have provided inspiration (and a few do’s and don’ts) for anyone looking to fulfill their own maddened desire to create an occult alphabet.

All the above “facts” that I have stated (and likely overstated) were gleaned from various Wikipedia pages including the one on Ibn Wahshiyya and the following two sources, the second of which is,surprisingly, less credulous than the first:

https://echoesofegypt.peabody.yale.edu/hieroglyphs/kitab-shauq-al-mustaham-fi-ma-irfat-rumuz-al-aqlam-long-desired-fulfilled-knowledge

https://booksofmagick.com/kitab-shawq/

I think that is about enough of my half-baked speculations. I have too many of my own hobbies to keep going down this rabbit hole. It certainly is fun though.

Dunstan

PS- I think your “Pre-Radiocarbon Expert Opinion” Chart would be much more impactful as a Gantt chart. Then it would be clear at first glance that almost everyone got it wrong.

Dunstan: This is all fascinating, and I intend to give it the attention is deserves. But do to “life issues”, and other demands and responsibilities, I’ve seriously fallen behind. But I want to read again, and respond in more detail, as soon as I can. Later, Rich.

Hi, Dunstan: Well, I had a chance to read more carefully through your last comment, and it was a steep learning curve for me! I think that overall, the books and the information about them and the authors, has at least further opened my eyes on several issues, not the least of which is the shear mass of unknown, unattributed, and some possibly invented, script and languages.

Today we can roughly categorize these, for the most part, into language groups, or fictional, and so on. But back in day, and for centuries, they were far more confusing to scholars. Point being, to me, this old/new disparity of understanding further emphasizes a point I’ve made: What would have qualified as an “unknown script” to a, say, 17th century scholar is very different to what one would look like to an early 20th century one. And therefore, it is stunningly improbable that one unknown to Baresch, Kinner, Marci and Kircher, would also happen to be in the Voynich.

Anyway, maybe that is just me… and I know it is not your point, here. As for whether or not these are authentic, or spurious, or what their provenance and influence may really be, are all issues I admit that is a deep rabbit hole I can’t investigate, and so, not comment intelligently on.

As for “The Long Desired…”, I found a copy on archives, and on page 69 or 70, there is a GALLOWS! This is both a curious and rare feature of the Voynich, so finding this example is actually pretty surprising and interesting: https://archive.org/details/KitbauqAlMustahmFMarifatRumzAlAqlm/page/n69/mode/2up?view=theater

I see what you mean about these “Gantt Charts”, and how it would be clearer and less confusing for the use of demonstrating the issue of lack of expert opinion backing up the C14. Thanks. An interesting thing about this issue: I have been having a marathon comment discussion over at the Ninja forum, and among other things come to realize something that seems obvious at first, but while it has been a facet of this issue of expert opinion, for some reason I had not phrased it as such. But I realized, in fact, this is a separate Red Flag of forgery, in a different way than I had previously expressed it. I think I had been, like many, sort of hypnotized by the very claim I have disputed, and so it eluded me. But really, “The fact that the overwhelming number of experts dating opinions do not match the radiocarbon results for the parchment of the Voynich, is strong evidence it is a forgery”.

Yes, in a way, in several ways, I really had been implying this, tangentally… but this is different than noting the fact the bulk of opinion differered from each other, and that this was a red flag, is somewhat different. More importantly, really, is that they didn’t match in the first place. Does that make sense? I had been so busy pointing out that the actual case was NOT showing genuine, that I was missing the actual, root value of this, that it IS supporting forgery.

Anyway, if you have any intrerest in wading through an agonizing 28… so far… pages of discussions about my Experts blog post, and just about everything under the sun, with some heavy hitters in the Voynich field pummeling away at me… it is a microcosm of the whole debate of forgery/genuine, I think… check it out. But don’t chime in and agree with anything I say there, because, apparently, you will be a “flat Earther” sexist, who is infantilizing your opposition. And more. It is one. wild. ride. https://www.voynich.ninja/thread-4213.html

Anyway, thanks for the information, and I apologize if I have not fully commented on all of it, nor fully utilized or understood all the implications. I’m stretched so damned thin right now, and try as I might, I know I miss a lot.

All the best, Rich.

Rich, Dunstan.

Dunstan – thanks for sharing the reference. I’d like to talk to you in Rich’s mailing list but here’s ok too. (A persistent glitch when I try to sign in. Rich has also tried to sort the problem, but no better luck).

I do understand why some people have started describing the quires’ writing surface as ‘calfskin’ rather than as vellum, because while vellum *is* made from the skin of a calf, not everyone knows that, or understands about there being two kinds of ‘vellum’ – uterine and non-uterine. The matter is complicated further by the fact that the custom of the English-language tradition is that while ‘vellum’ means membrane from the calf, you add ‘uterine’ to denote when the skin has come from an unborn calf. In the German tradition, though, it is uterine vellum which is the default, so ‘vellum’ is *presumed* uterine, and there have been some amusing moments in online conversations as a result.

Point is that there’s nothing remarkable, in the least, about the fact that the quires’ writing surface came from the skin of a calf. Much parchment did, and all vellum, too. The word ‘vellum’ comes, I believe, from the same root as ‘veal’.

Why should this matter? Is it nit-picking? No – because while all parchment, and all vellum is ‘membrane’, and some membrane is finished as parchment, and other membrane as what we call [non-uterine] vellum, production was not uniform throughout history nor even throughout medieval Europe. So whether you have ‘parchment’ or ‘vellum’ or ‘uterine vellum’ is another pointer to where, and when, the writing surface had been produced.

We have to distinguish ‘skin’ or ‘hide’ from ‘parchment’ and while there are reasons that librarians get a bit jittery about the line between ‘parchment’ and ‘vellum’ (it’s a spectrum, rather than a line), the difference is evident and the Voynich quires have always been known to be of vellum (in the English sense).

The quality of finish is also an important factor and – though it’s much harder to see on the current (2nd-set) of Beinecke scans or the Beinecke edition, where these are more bleached-out, the fact is that the vellum used for the Voynich quires is imperfectly equalised and you can still see hair follicles in many pages.

This is also a telling point in regard to provenance and a negative item for those arguing for German provenance – not a disproof of that theory, but an item against it because German parchment(s) are renowned for achieving near-perfect equalisation by (from memory) the 12thC. There’s also the issue of dimensions, and whether the regular quires were made for the copyists from larger sheets of vellum or were provided them in the form of pre-cut quires, as suppliers in Europe were doing from (at least) the fourteenth century. This is significant because the standard measures used for such quires (and which also come close to those used for paper) differ from region to region within Europe. I’m not claiming to be a qualified historian of codicology and much more needs to be done here, but I did look into the situation which applies in mid-fourteenth century Italy and France as well as parts of the Aegean, with some interesting and consistent results.

To describe the Voynich writing surface as ‘calfskin’ – rather than more precisely as vellum (or even as parchment) blurs the significance which others, better informed, are likely to take from a statement like that.

Also, the term ‘calfskin’ applies generally to skin given a tougher finish, such as by tanning, so that we speak of ‘calfskin bindings’, but if we say a text is written on ‘calfskin’ it would normally be taken (as by an archaeologist or an art-historian) to mean that the surface had been skin, or leather, but not parchment or vellum.

In any case, it isn’t the fact of the writing surface coming from the skin of a calf that allows us to say the Voynich quires were inscribed in a Latin context, but that they were inscribed using a quill.

You can find parchment over half the Mediterranean world – I’ve seen items recovered from Greco-Roman Egypt on which the script was Persian – but they were not written with a quill. People were using iron-gall inks all through the Mediterranean world, and oak-galls were imported as far as Persia during the medieval centuries for that purpose as well as for tanning etc. But again – not written upon with a quill.

Hope some of this is of interest. I really would like the recent ‘calfskin’ habit to be dropped. It isn’t precise enough, is potentially misleading, and allows poor arguments to get by which wouldn’t survive otherwise.

Diane,

I’m very surprised that the first tomato hurled in my direction after that post was taking issue with the term “calfskin” but I’ll take it. Thank you for your consideration and the information about differences between calf-skin, vellum, and parchment. I didn’t intend to contribute to the misuse of the terminology. I personally used calfskin as a catch-all term because I wasn’t sure what exactly the Wellcome St. Cyprian was written on, and to try too find out would have required effort on my part. I certainly wasn’t trying to imply they were the same batch of material or even the same grade or quality. In any case, it seems natural for the Voynich manuscript to be written on vellum but it seems less natural for the Wellcome St. Cyprian demon summoning manual, which was written in the late 18th century, to be written on parchment or vellum, or even written at all. It seems fraudulent to me (and it has a foldout). I will certainly admit, that to cite “calfskin” as a similarity between the two manuscripts is a big stretch. Although, in the context of my post, which was wildly speculative, it didn’t seem out of place.

I am not a serious researcher or even a casual one. But I greatly respect and appreciate the work the professionals and serious amateurs have done on this subject. As for me, I have just stumbled across some interesting things in my own unrelated “research” that may or may not have any bearing on the origins of Voynich manuscript, particularly as it relates to the modern forgery angle. I think maybe the shadowy, cryptic, and inherently insincere world of magical texts and grimoires could possibly lead to some sort of progress on this front.

Dunstan

PS- I see that you have written some articles on the origin of playing cards. I look forward to reading them. I was in Eastern Sicily few years back, and bought everyone I knew a Sicilian deck. Although, I don’t think everyone was as fascinated as I was with the coins, cups, cudgels and swords.

Dunstan, Most of my professional work was done on commission, but unfortunately the chap who asked me to research the history of those images became seriously ill before the business was complete, so all rights reverted to me. I made a couple of articles from it and gave them to a specialist, and gave a couple of university talks, but that was more than twenty years ago, and I’ve forgotten most of it now. 🙂

The ‘calf-skin’ thing isn’t a ‘tomato’ aimed at you, particularly. It’s just fyi sort of information.

In my opinion an expert on the manuscript should be able to translate it and explain how they did it.

if you go here: https://ling.auf.net/lingbuzz/008025 and click on the pdf

Astrology Series, No. 4. MS 408. – lingbuzz/008025

Astrology Series, No. 4. MS 408. Gemini: The Lovers. This paper translates all scripts and image annotations included on the Gemini page from the astrology section of the manuscript.

I would be interested in what you think about this work.

Keith Henson

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Keith_Henson

Hi Keith: I went to download the paper, and notice it is by Gerard Cheshire. I’ve already seen his work on two occasions over the years, but will take a look again. He had asked me, and many others to review his attempts at translations, but no one believed the system and results had any merit. They were not repeatable, as relied on the purely subjective choices from several languages, at the “translator’s” discretion.

Nick Pelling and I are not often on the same page, but I agree almost entirely with him, in this case: https://ciphermysteries.com/2017/11/10/gerard-cheshire-vulgar-latin-siren-call-polyglot

Nick’s results, and analysis of this attempt… and for that matter most people who were tasked with reviewing it… universally agree there is no way this is a translation of the Voynich. But as I said, I’ll download the paper and take a look later.

Thanks- Rich.

What I find of Cheshire’s work is that it makes sense. He makes a case for the manuscript mostly being a woman’s health manual with a section on a rescue mission for people caught in a volcanic eruption.

I have made a case to Cheshire that the style of writing is too advanced to be the only example. Since he makes a case that the people who wrote it came from Aragon, I have suggested that someone go through the archives there to see if there are any similar manuscripts. (My wife is a professional archivist.)

Rich,

about the forum – I’m receiving emails about forum threads, and the ‘experts’ discussion is really interesting, but the glitch is still happening – that is, the ‘change your password’ email doesn’t turn up.

Re-reading these comments, and harking back to yours of March 26, 2024 (9:06 am) I agree with your ‘back to front’ comment. I have always found it more helpful to ask ’where and when *do* we find such-and-such’, instead of (as you say) ’how can I get z theory to accommodate such-and-such?’.