In my last post, I explained the reasons I believe that the popular quasi-historical 1904 work The Follies of Science at the Court of Rudolph II served as the “primer” which was used to create the Voynich Manuscript. Although the forger didn’t use images from that work to copy, I contend that they used the stories and references in Follies as the chief guide for creating the Voynich. This was done to make a book that looked as though it came from the Court of Rudolph II, and probably at the hand of either Jakob or Christian Hořčický (although Christian, Jakob’s father, seems to be an invention of Bolton). This is before Wilfrid changed his mind about the authorship, and decided he would push it as a Roger Bacon work instead. My speculation as to the reasons for that change are subject for a future post.

The list below includes the Primer, and then a selection of other sources for the imagery found in the Voynich. They all have one or more of the below characteristics:

- The item, person, activity can be directly traced back to Follies, the “Primer”, and or:

- The item is in some work, or in a work by some person, mentioned in Follies of Science at the Court of Rudolf II, and or:

- The item in the Voynich is related to the disciplines, activities, and items which would would reasonably expect to be found in the Court of Rudolph II, as imaginatively conveyed by Bolton in his faulty work.

- The item would, by being in the Voynich, fulfill the goal of the forgery, i.e., to look as though the book came from the Court of Rudolf II. That is, there is a reason behind these comparisons, that supports them being correct.

- Multiple comparisons sometimes come from single books as sources, further supporting the correctness of the hypothesis.

The fact that, through Follies, all these images from the Voynich connect to Bolton’s vision of the Court, and to each other, gives them context, and vastly raises the possibility that any one of them, or all of them, is purely coincidence, paradiolia, or wishful thinking. These connections, to each other, and the Court, strengthen these identifications of them in the context of my hypothesis.

The Follies of Science at the Court of Rudolph II, 1576-1612, by Henry Carrington Bolton (1904): Covered in detail in my last post, I believe this was the Voynich Manuscript “primer”. As I’ve pointed out, almost each and every one of the items, sciences, people, events, and more, which a great many people have suspected appear in the Voynich, can also be found in “Follies”, or as a discipline of someone mentioned in the book. It is not, however, a direct source for the images themselves. Follies was a very popular book, and many learned Bolton’s version of the colorful goings on in the Court of Rudolph II through it. It could be imagined that any equally colorful grimore which had been born in that Court would have had a great interest and value. And to this end, I believe this work was used as a guide to do just that, in the form of the Voynich Manuscript.

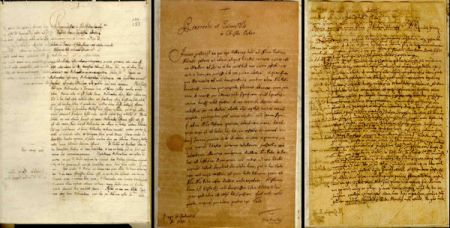

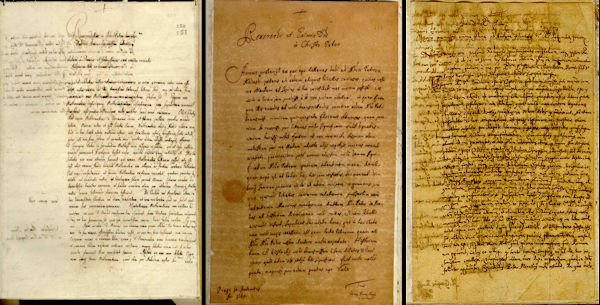

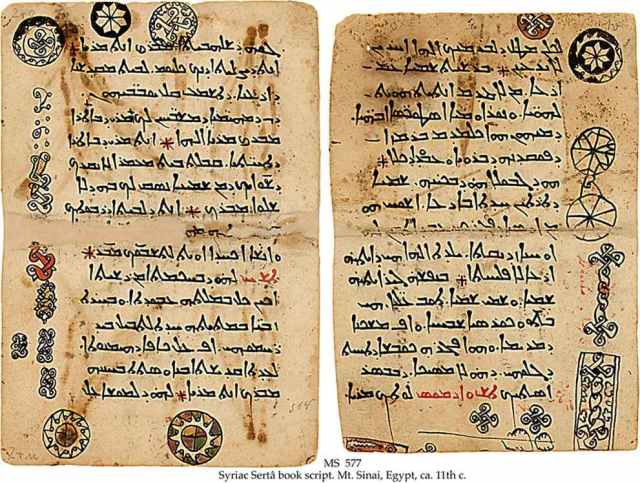

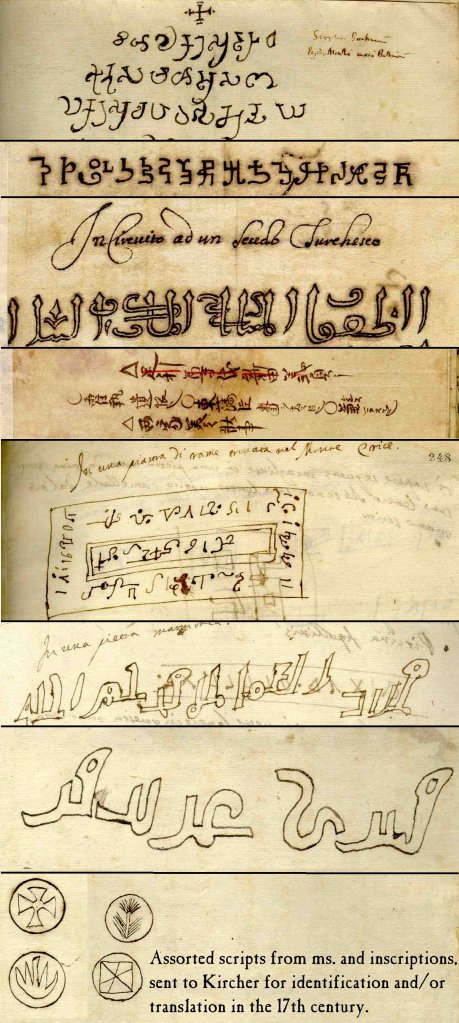

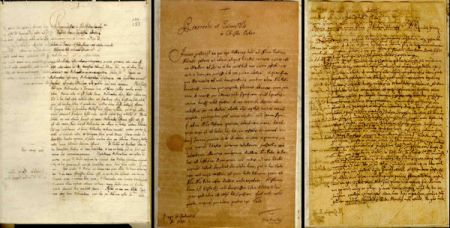

The Letters of the Kircher Carteggio: While the contents in these letters are a very poor and incomplete description of the Voynich, I still think they were part of the inspiration for creating the Voynich Manuscript. Forgers sometimes create items to fulfill a gap in history, such as an item which was referenced, but now lost. Doing this lends credibility to their creation because it creates instant provenance. The provenance here is actually very poor to non-existent, and even in some ways these descriptions against them being about the Voynich. But since many believe them to refer to the Voynich, thus serving the purpose of the forger (if that was the intent), I include them here as a possible source.

Without knowing exactly how Wilfrid came to know of the Letters, one possible scenario is through his friend Strickland, who was in charge of the Villa Mondragone at the time Voynich claimed to have found the manuscript there. Voynich was well known for “having his feelers out” for possible rare book finds, and he was certainly good at finding them. So perhaps one of the Jesuit professors, or Strickland himself, in studying those letters, realized some were discussing a now missing herbal, and this was imparted on Voynich. It could have been though any number of other possible means, however.

This of course excludes the 1665 Marci letter, which may be a forgery used to change alter the intended authorship of the Voynich from Horcicky to Roger Bacon, and cement a desired Rudolph II ownership. It is also important to point out that whether or not the Voynich was presented in the originally intended incarnation as a work created in the Court of Rudolph, or as presented, as a possible work by Roger Bacon, the Letters of the Carteggio would serve equally well to back up either story line.

Athanasius Kircher is mentioned on page 93 of Follies.

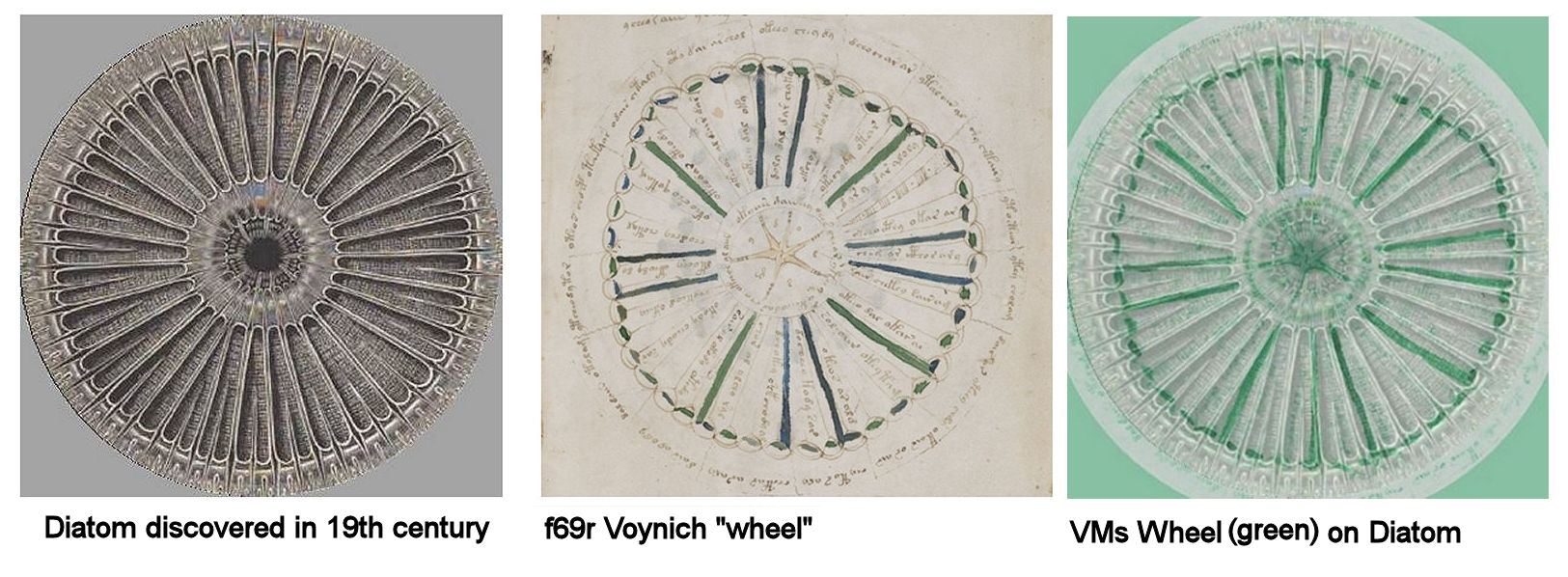

The Microscope And Its Revelations, William B. Carpenter (later W.H. Dallinger), 1856-1901: Long before I believed the Voynich Ms. could even remotely be considered a forgery, one image from this book gave me pause for concern: An engraving of a certain diatom, found in the 19th century off the coast of Japan, and magnified at 512x. It is so small that it could not have even been seen until microscope advances well into the 19th century.

Many before me have noted that many Voynich illustrations seem to be of microscopic cells, diatoms, and other plants and organisms. Most of these were not seen until the late 17th century with the invention of the microscope. In fact the diatom was not discovered until then.

All the major, and some minor features of this diatom line up very well with the features of the f69r wheel. The spokes, the central “star”, all diameters (including the outer “writing” on the Voynich image), and even the little “pod like” ring, all match up strikingly close to similar features on the other.

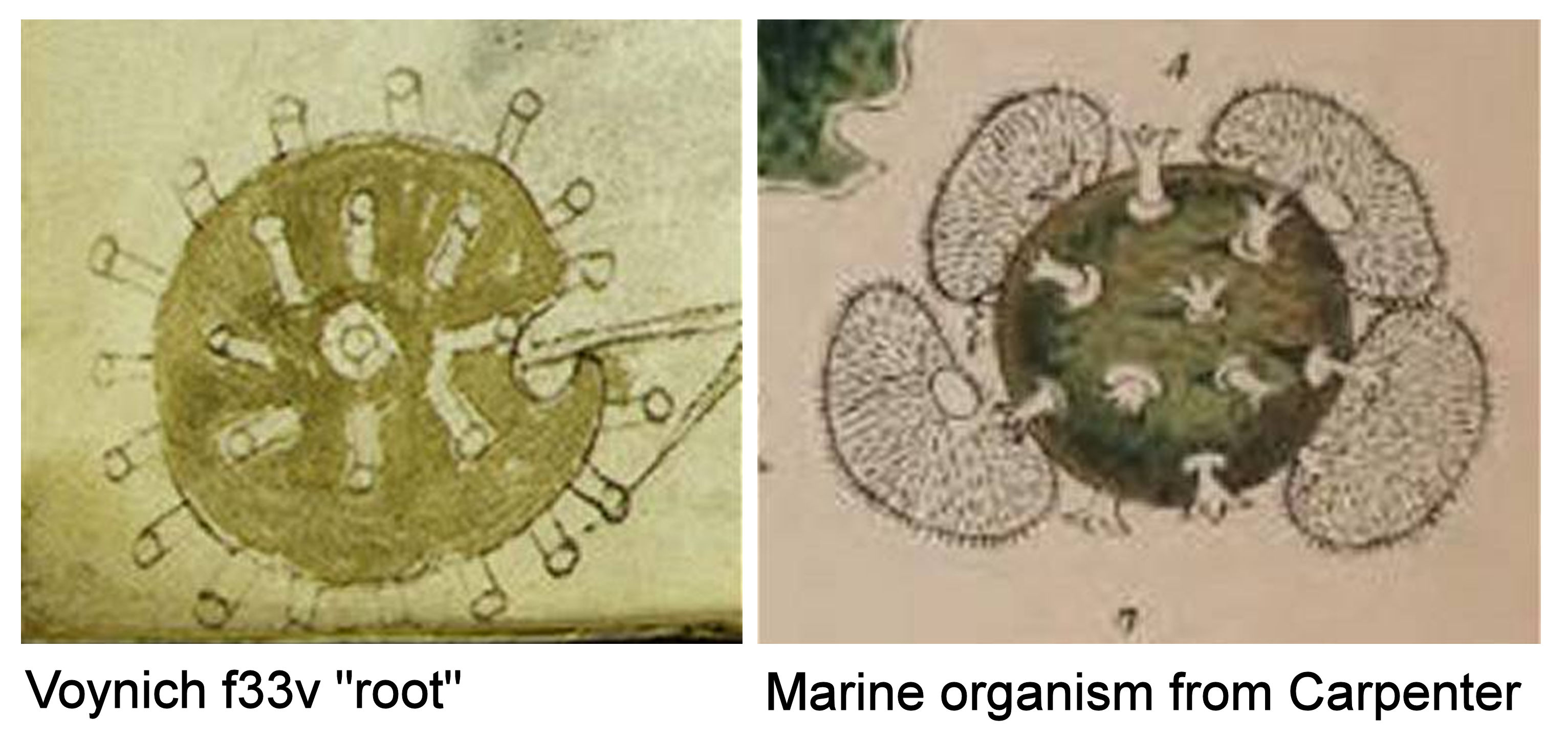

And there are several other comparisons from this book, but I’ll list one more, here: The odd “sunflower” root is strikingly similar to the marine organism found in Carpenter. The below scan of the organism is from a copy of Carpenter with colored plates, and both are green.

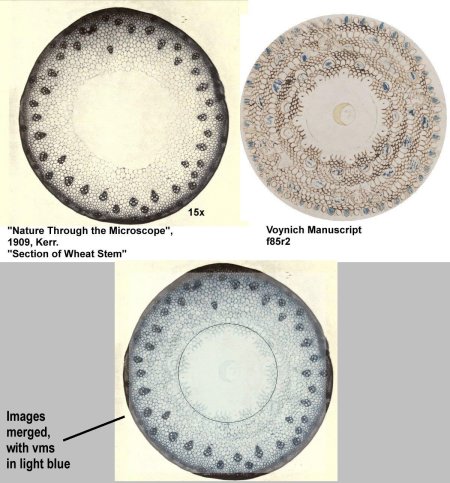

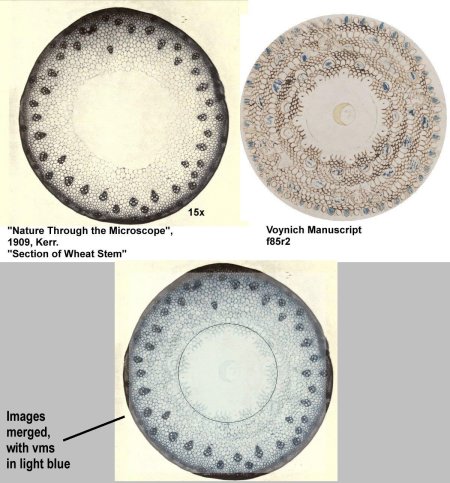

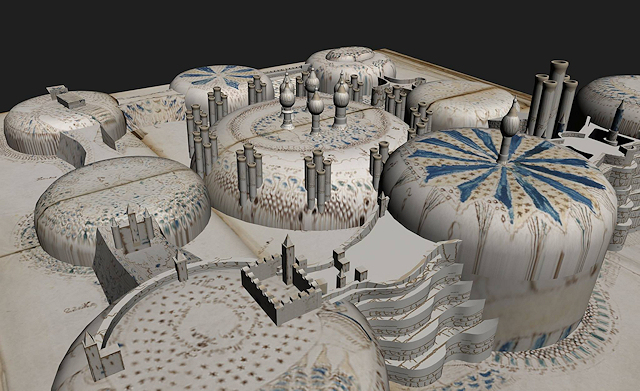

Nature Through Microscope & Camera, Kerr, 1909: Like the above book by Carpenter, this seems to be a source of several Voynich illustrations. For the example below, a wheat stem cross section, I think the use was to represent the concept of the microcosm/macrocosm. The stem was used as a farm, seen from above, as one of the rosettes. We know this as there are several figures in it, picking or holding some plant items. The farm would be the macrocosm, associated with the microscopic image of a grown plant. I think several of the Rosettes images can be similarly matched to certain wheels found in other places, for a similar purpose.

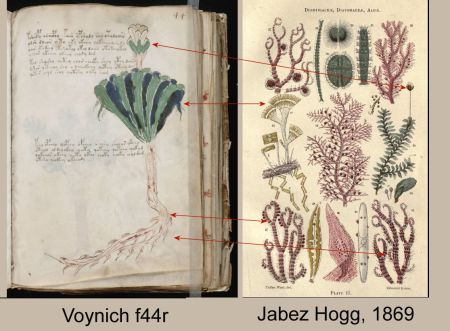

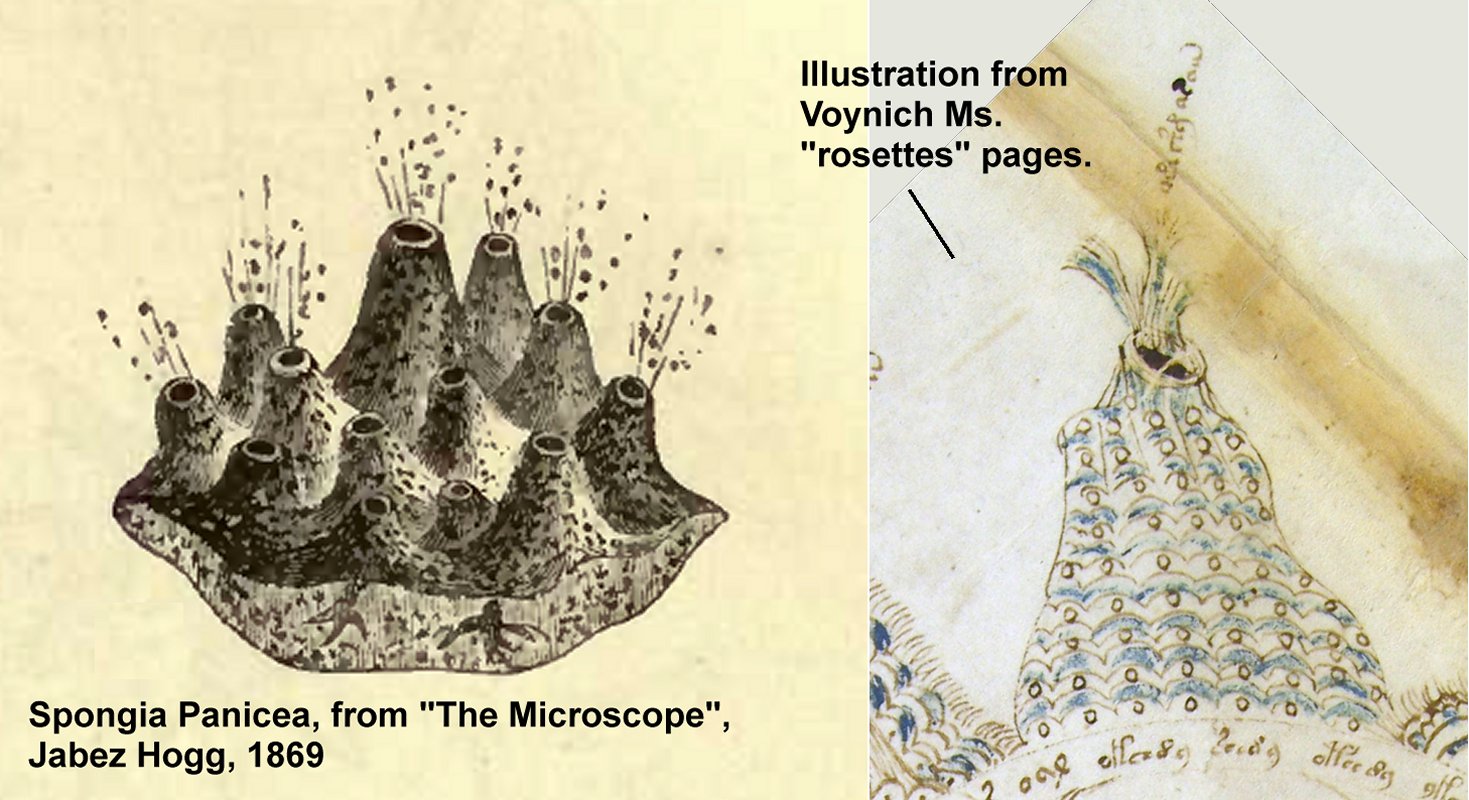

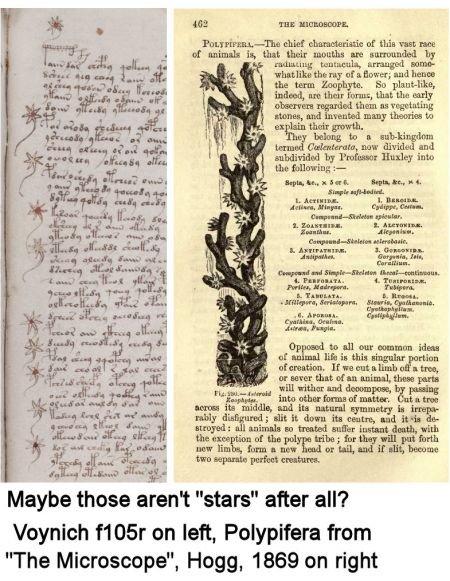

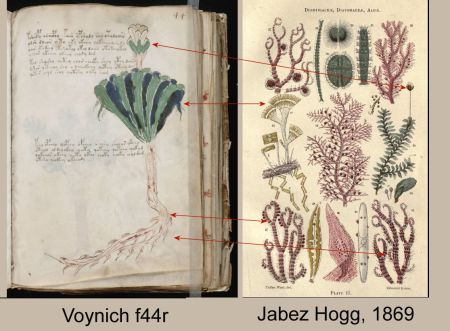

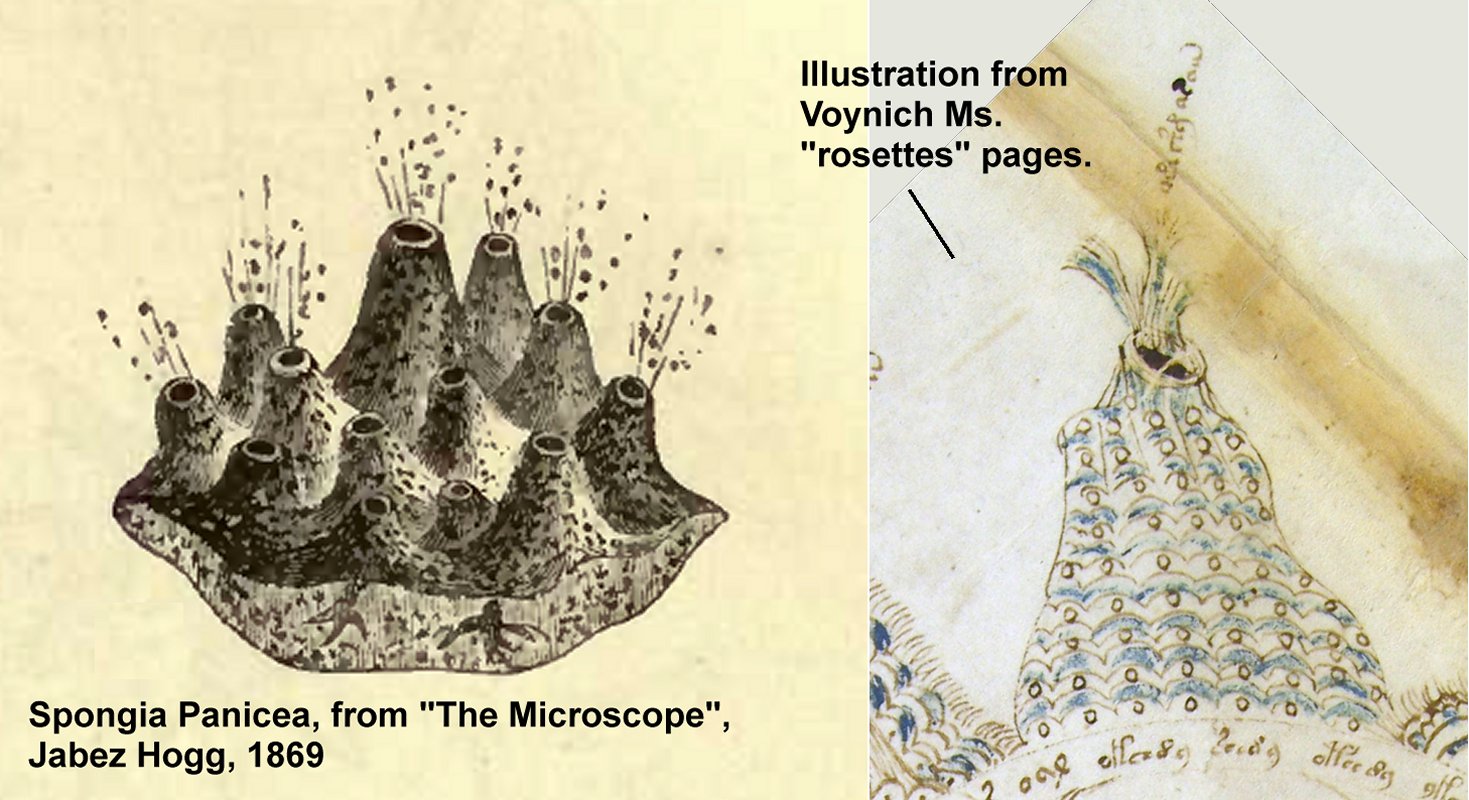

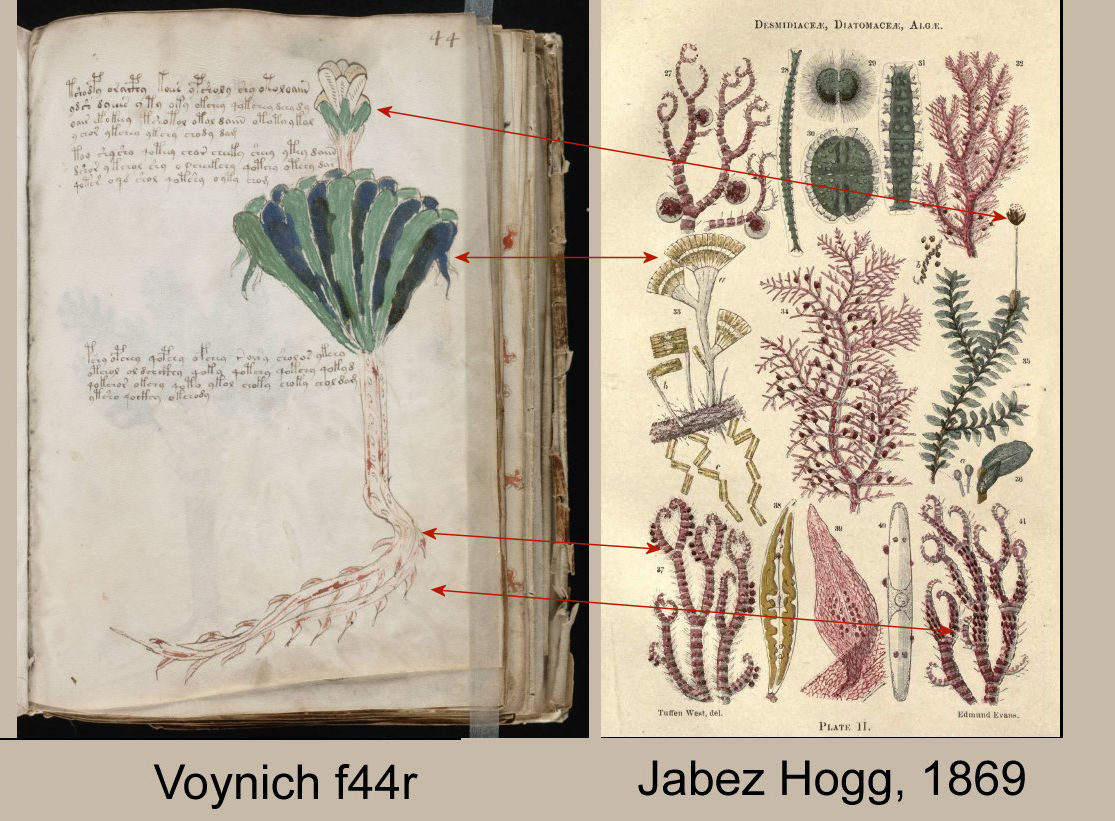

The Microscope, Jabez Hogg, 1869. There are several good comparisons from this one book.

It as though the Voynich illustrator assembled the f44r plant, above, from parts found on the plate from the 1869 Jabez Hogg book.

Above is another great comparison from the same Hogg book. The “volcano” is found on the rosettes pages.

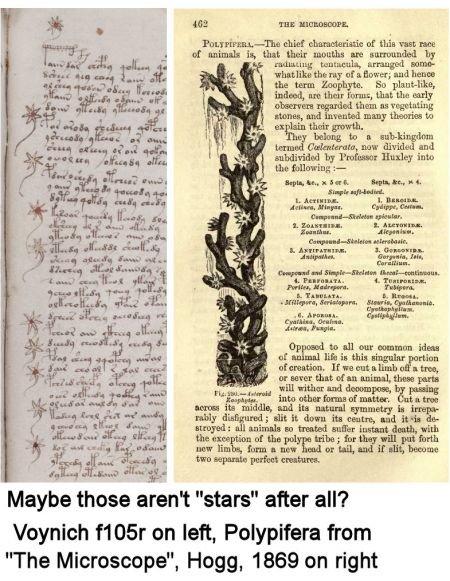

And here, yet another, from the same book. The Voynich plant has standing leaves of similar shape, on a “floating” platform, with a similar-shaped flower pod. Is it an exact match? No, of course not. But the two concepts are very unusual in themselves, so to find those elements both from the same page of Hogg, and then find other good comparisons from the very same book, simply strains coincidence. And below is yet another comparison from Hogg. We have the “stars” from the Voynich, the source for same long sought after. Is this the actual source? Maybe those are not “stars” after all, and it is that the Jabez Hogg book was the source? Here I think they compare well to the Hogg images of Polypifera, which also have seven spikes, centers, and even the mysterious “strings” could be borrowed from the illustration on the right.

The above books on microscopy are not alone, but only a suggestion of possible actual identifiable sources. But a quick google search for antique microscopic images of all types… plants, animals, diatoms, cells… will offer up a dizzying array of “Voynich-like” images. And the idea that the Voynich seems to be filled with such microscopic representations predates my time on this planet by several decades. Why? Well, simply because they do like just like this, and look less like anything else suggested. And those alternatives suggested, I would further argue, do not have an overall context which explains them, other than, perhaps, the New World theories. But even those ideas leave many other images unexplained, and unaccounted for, which this theory does not.

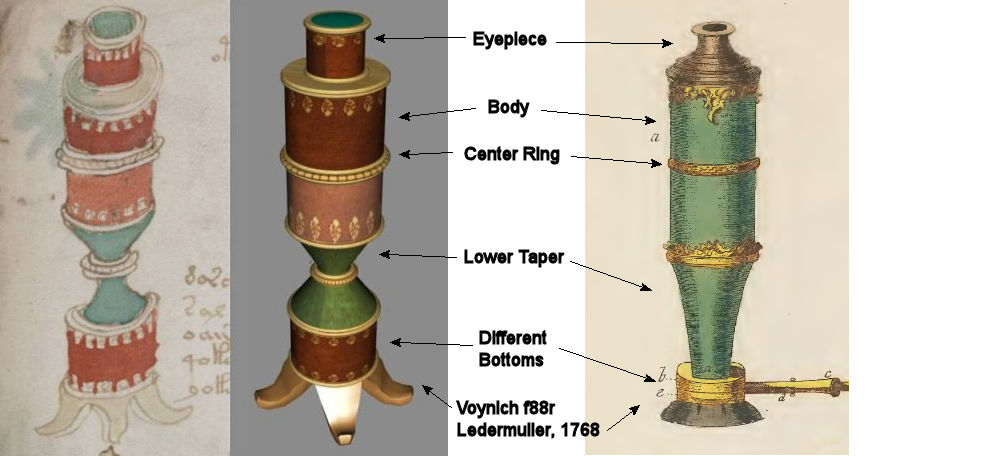

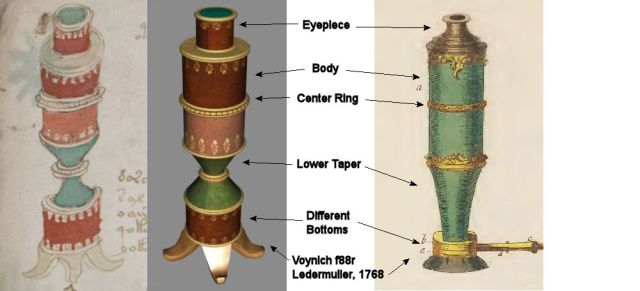

The Green Microscope: I have long been intrigued by the striking similarity between this green microscope and a Voynich illustration… even the colors, proportions, and more. So imagine my surprise to learn, years later, that the actual device was a pleasant stroll from Wilfrid’s Florence Libraria, only a quarter mile away, while he was there! I also find it interesting that the colors do match, because of course in 1909 most books were in black and white, so most forgeries from books at the time got the color wrong. There are many cases of this, in which the forger only had a black and white engraving or photograph to work from, and so, got the colors wrong. The only way to know the right colors would be to see the object, or have it described. And in this case, and the f33v root, we have colored sources, AND similar Voynich images which are in the “right” colors.

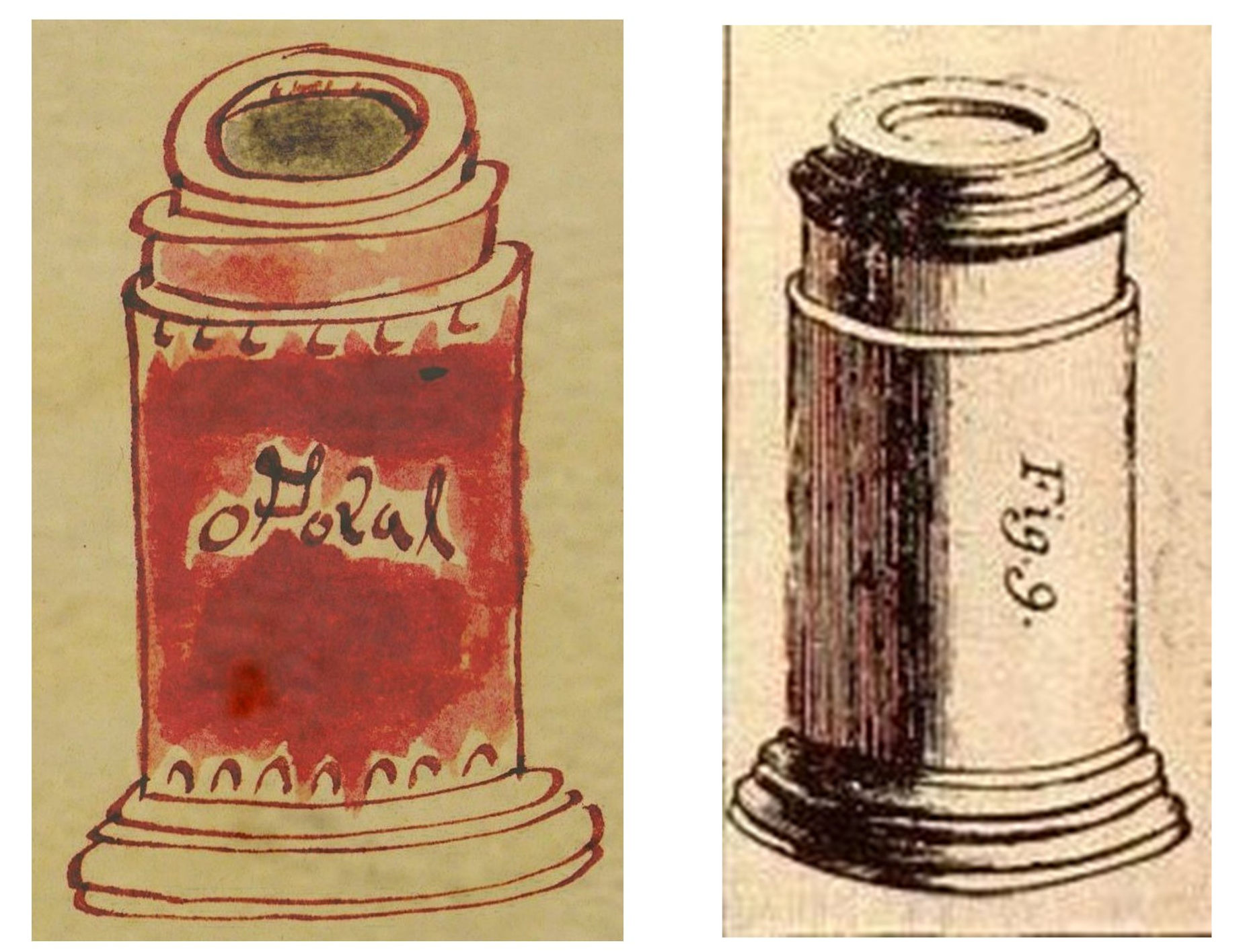

Broadsheet of 1763, Pablo Minguet: There are many comparisons to parts of optical devices, both microscopes and telescopes, in the Voynich. But the one below is one of the most inclusive of all elements: Recessed tops, parallel sides, stepped sides, ringed ends. Even the proportions of both are very close. Yes, many Voynich cylinders also have legs, as seen below, but legs of this type are also a common feature of early microscopes. Furthermore, those real microscope legs are often in the “delphini” (dolphin) motif, which the Voynich legs often resemble.

To further illustrate my point, I will show below my own attempt. I drew one of the 18th century opera glasses in (my imitation of) the style of the Voynich artist. OK not a great match to the “Voynich Style”, but I think it serves to illustrate the above point from the opposite direction: That these cylinders could be copies of the engravings I identify.

Amusemens Microscopiques, 1768, Martin Ledermuller. This particular instrument does not seem to appear anywhere but this volume. While some elements of it are different than the f88r Voynich cylinder I compare it to, it does share some very specific elements, as shown below. And it is actually a closer match to that Voynich cylinder than my 3D rendering of it (center image). My version is a bit wider than the Voynich cylinder.

Those are very specific, and also unusual, features. The fact that so many Voynich cylinders share so many such features with early microscopes, and that some of them are very similar to certain illustrated and actual models of them, is close to impossible to dismiss with claims of coincidence.

Why would optics and the things seen through them, be in the Voynich herbal? The motive would be because the Bolton vision of the Court of Rudolph was projecting a place and time of exciting and ground breaking experimentation in the proto-sciences. More specifically, Bolton includes discussions of Drebbel, Roger Bacon, John Dee, Baptista Porta, and Kepler, touching on, among other things, their interest, invention, experimentation and studies in optics. Anyone making a forgery to look as though it was born of Bolton’s court would want to include these optical references into it.

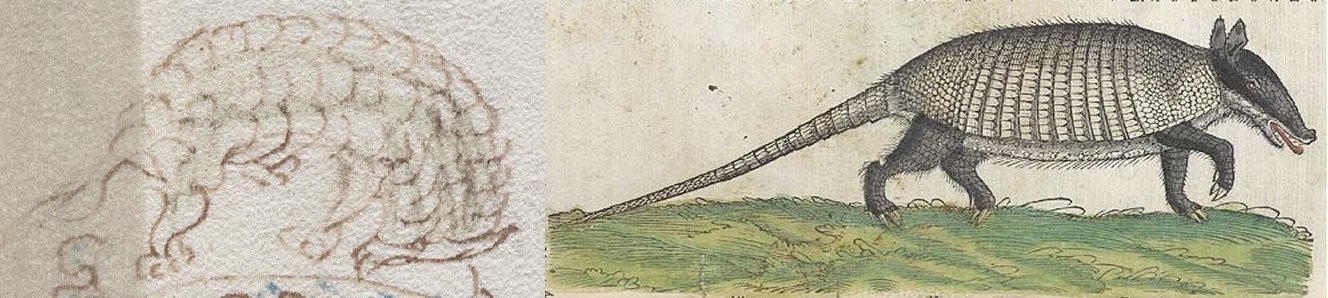

Conrad Gesner’s Historicum Animalicium:

Ah yes, the poor abused armadillo. Of many armadillo illustrations, I feel this Gessner version is the best overall match to the Voynich f80v animal. Note the upturned snouts, the pointy ears, the curved shape of the head. I thought this long before realizing that the book this is from is actually mentioned in Follies! From page 212,

“Conrad Gesner, Professor of natural history at Zurich, whose “History of Animals,” published in 1551, is the basis of all modern zoology; his younger contemporary, Ulysses Aldrovandus, who held the chair of natural history at Bologna, published six large folio volumes illustrated with wood cuts of many of the animals, his descriptions being in part taken from the work of Gesner.”

And yet again, as a guide the Bolton Follies would provide direction to a source for animals to include in a forgery “from” the Court of Rudolph II.

Adriano Cappelli’s Lexicon Abbreviaturarum: This book has often been cited as a great example of the Voynich’s famous “gallows” characters. These odd glyphs are really not seen anywhere else… although isolated examples of similar shapes have been found in scattered locations. One of these other examples has been noted by Berj Ensanian in the Journal of Voynich Studies.

However, I think the examples in Capelli may be the source inspiration of the Voynich gallows. And they were used incorrectly, wherever they are from: The usage of these gallows in the Voynich seems to be intended in a meaningful way, while the use in the 1172 contract was purely decorative. Cappelli’s Lexicon was published in Milan by Ulrico Hoepli. Hoepli was also a rare book dealer, and would have been known to Voynich.

Photographs of Stars, Star-Clusters and Nebulæ, Isaac Roberts, 1895: If, as many believe, the “wheel” on Voynich f68v/1 is a representation of a distant galaxy, by someone with advanced optics of previously unheard of power, then I would contend it is there to yet again meant to imply that the Voynich Manuscript was a document of the Court of Rudolph II. And as I wrote in my post, “Newbold’s ‘Nebula'”, the source is probably Isaac Robert’s Photographs of Stars, Star-Clusters, and Nebulæ.

Follies of Science mentions optics, and specifically telescopes, in several pages. On page 87,

“The appearance of a brilliant comet in 1607 (since known as Halley’s comet) greatly alarmed the citizens of Prague and threw the credulous court of Rudolph into consternation; the Emperor sent for his astronomer, and from the balcony of the Belvedere they studies the celestial wonder with the aid of a powerful telescope…”

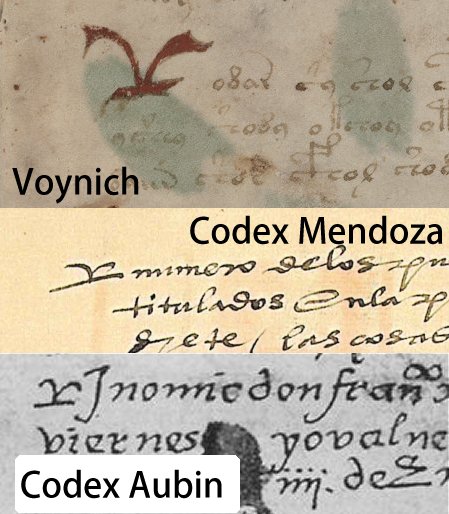

Aztec Codices: Many have long noted similarities between illustrations and writing in the Voynich to various Meso-American Codices. In fact it forms the basis for several well known theories, among them those of Jim and John Comegys, who postulate that a form of Nahuatl may be the language of the Voynich. Jules Janick and the late Arthur O. Tucker identified hundreds of plants and other items as being Pre-Columbian New World species, in two works: The Flora of the Voynich Codex: An Exploration of Aztec Plants and Unraveling the Voynich Codex. Before that, Tucker worked with Rexfort Talbot with a similar theory linking the Voynich to Meso-American Codices, most notably the Badianus Manuscript. The researcher Stephen Bax was another, and there are several more. Inclusion of such references and influences in a Voynich forgery meant to look as though it came from Bolton’s Court of Rudolph II makes perfect sense. This, because New World plants, animals, medicines, and culture are all mentioned in Follies. As one example of this, on page 146,

“The little explored New World across the Atlantic had begun to contribute its valuable remedies, notably china root, cosa, sarsaparilla and tobacco”.

And the inclusion of these items, for the purpose I content, is ther reason that many people have noted that said plants are in the Voynich. Not only that, but they are often closest to the versions of these plants as drawn in New World herbals. Below is a page from the Badianus Codex, cited by Tucker, Talbot, Janick, Bax and others.

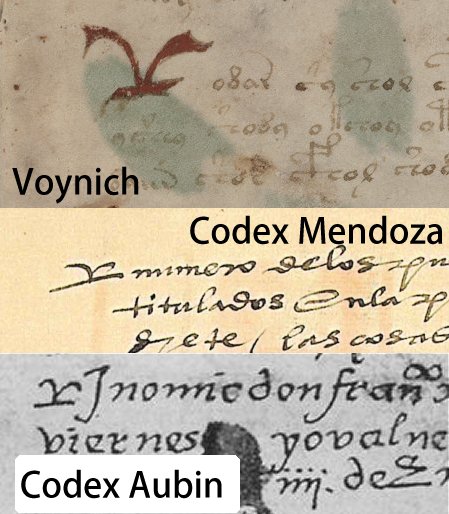

But is it not only the plants, or the writing, or the animals like the armadillo. Another example is what I call the “Bird Glyph” on f1r of the Voynich. This is strikingly similar to the paragraph marker used in Aztec works, which of course were only known sometime after the early 16th century.

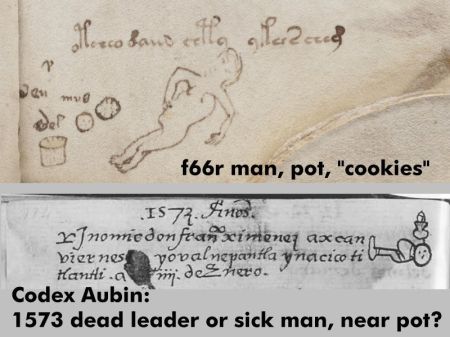

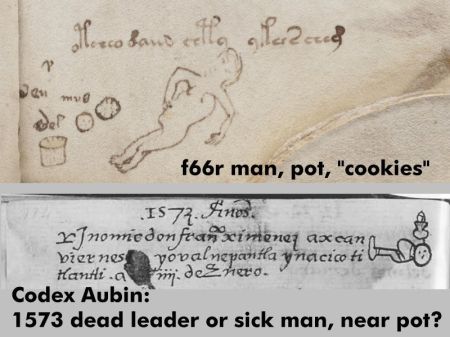

The Codex Cardona also has a “bird glyph”, and I think it is in others, too… while being a otherwise a really unusual shape. From the same Codex (to the right of the above clip) there is a very similar scene with a sick or dead man, by a pot, as seen below:

Other assorted Herbals: I can’t list all the herbals and botanicals that a great many experts and amateurs alike believe may have either been influences on the Voynich Manuscript, or used to make a connection to some genre in the field, or a geographical or chronological connection to it. The problem is, these herbal references are from all times, all places, by all people, of almost every plant known to man. So making such comparisons has not been helpful, to others, to determining the origin, authorship, geography, chronology, of the manuscript. Perhaps an exception is the case of the New World theorists, it has… and I agree… shown that this work must be post-Columbian, and contain American or Meso-American influences.

But the very fact that so many plausible, but highly varied sources have been identified, I contend points to the more likely possible that the Voynich is forged, and modern, because it cannot be from “all those things” unless it is forged.

I’ve already mentioned the Badainus Codex above. Alain Towaide wrote a section about the Voynich in the book, Villa Mondragone: Secunda Roma René Zandbergen wrote a review of that section on the site of the late Stephen Bax. In that review are some of the illustrative comparisons made between two herbals and certain plant illustrations in the Voynich. One is the early 14th century Manfredus de Monte Imperiali Liber de herbis et plantis, the other the c. 1440 herbal known as Sloane 4016. And I would agree that there are similarities. René further wrote about the Monte Imperiale, on his own site, “One striking similarity between an illustration on f35v of the Voynich MS and one on fol. 60r of the Paris MS BN Lat.6823 has been noted by several people…”, and, “While the Voynich MS illustration clearly isn’t a copy of the Paris MS, it is also inconceivable that it was not in some way inspired by this or a similar illustration in another MS.”

And one might think, then, that due to the dating an origins of these two works, they are supportive of the Voynich being 15th century, and Italian. But there have been a great many other good comparisons, and they are from a very many other times and origins. Among them are Ashomole’s 1652 “Theatrum Chemicum Britannicum; Materia Medica of Dioscurides, and its copies; Anthony Ascham’s (or Askam’s)1551 “A Little Herbal”, and many more. To cherry pick those which fulfill one’s pre-conception for the possible dating of the Voynich is to ignore a great many other herbals, with very similar images.

The New Atlantis (and other Utopian sources): This 1621 work by Francis Bacon has so many similarities to the iconography of the Voynich, that it led me to wonder, for some time, that the Voynich might be a sort of “homage” to that fiction. I did abandon that theory long ago, but still feel that the New Atlantis was some influence. Among these are grafted plants, strange plants and animals, the Rosettes fold out as a utopian map, Rosicrucian imagery, possible glossolalia, and more.

I do still think that the Rosettes pages are an aerial view, meant to evoke the early concept of a Utopian city. For a selection of these, see my post titled There’s no Place like Utopia (get it?).

Francis Bacon is mentioned in Follies, too, although The New Atlantis is not. Still, anyone using Bolton as a guide would reasonably follow it to Francis Bacon, and so may want to use influences from The New Atlantis to color it out.

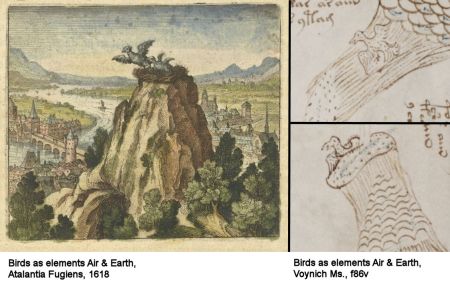

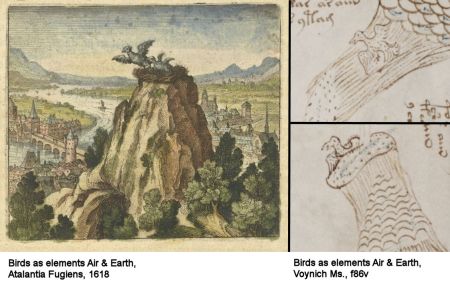

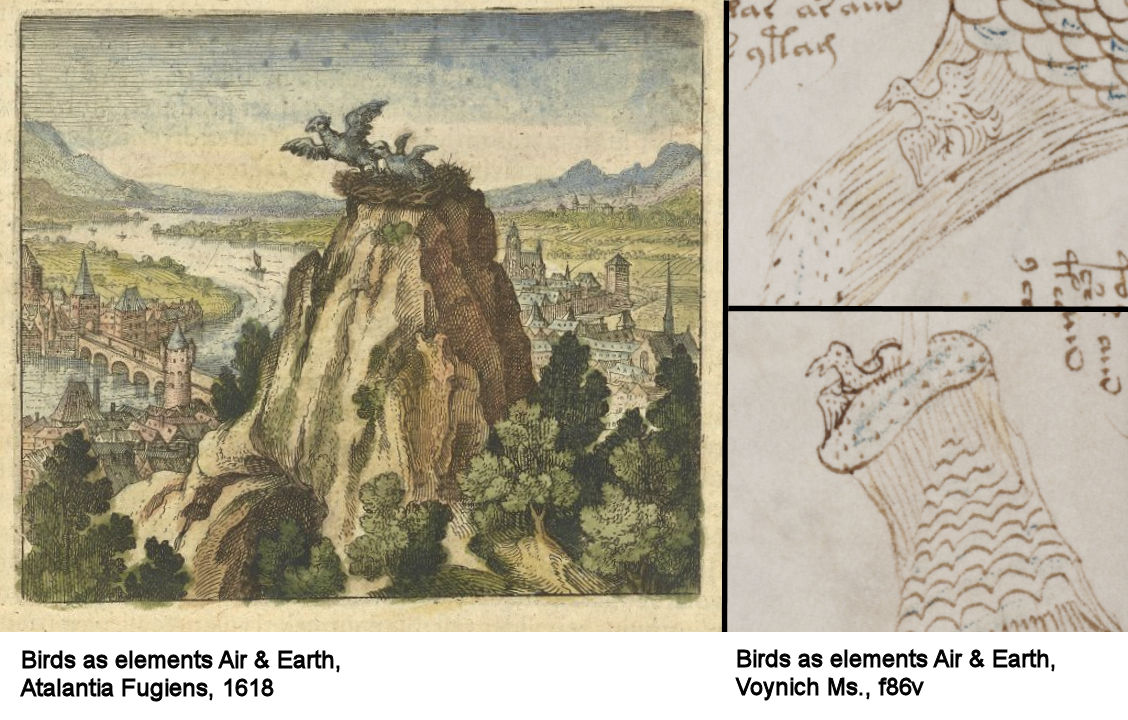

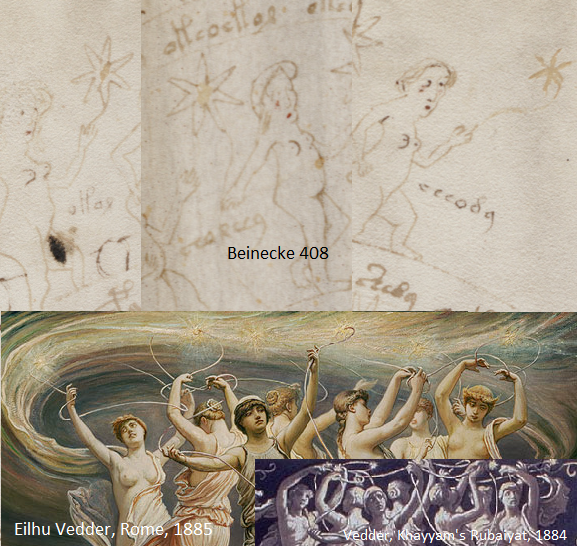

Atalantia Fugiens: This highly influential work by Michael Maier (1568-1622) had several publications. Here are some nice scans of a 1618 edition. The similarities in the style of some illustrations implies to me that this book was a source for several Voynich illustrations. But two of the birds in Atalantia is a speficially good one, even beyond the look and style (which is close to begin with). The possible association is further implied, as the birds are in the same context… sitting in and flying from a mound of some sort, while in the Voynich f86v illustration, one bird is on a mound, and the other is flying above it. But more importantly, in Atalantia Fugiens, the birds are used to illustrate the elements of Air and Earth, as they are flying and nesting. The Voynich birds are arguably also representing Air and Earth.

And Maier is mentioned on several pages of Follies, and an imagined conversation is related between him and several others. Atalantia Fugiens is mentioned on pages 161 and 164. The elements are discussed by Maier and the others, although they mention a different Fugiens illustration of them than the birds: four naked men carrying fire, air, water and earth. And Follies even has an illustration from Atalantia Fugiens.

So here we have yet another case of many, in which an illustration in the Voynich is very similar to content discussed or referenced in Follies of Science at the Court of Rudolph II.

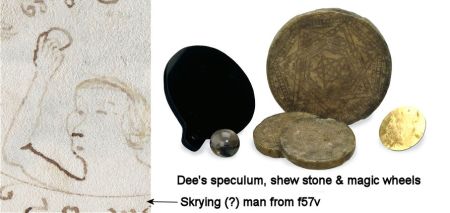

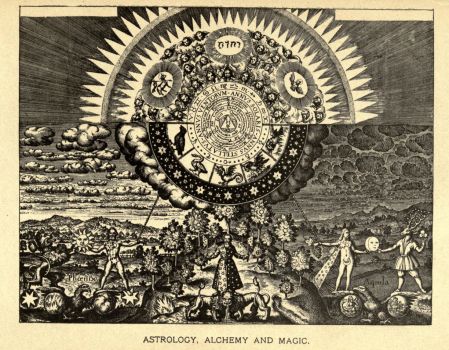

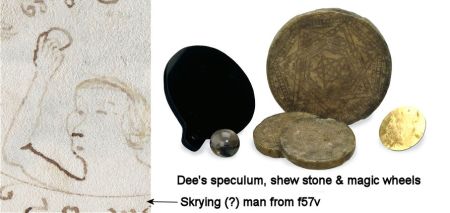

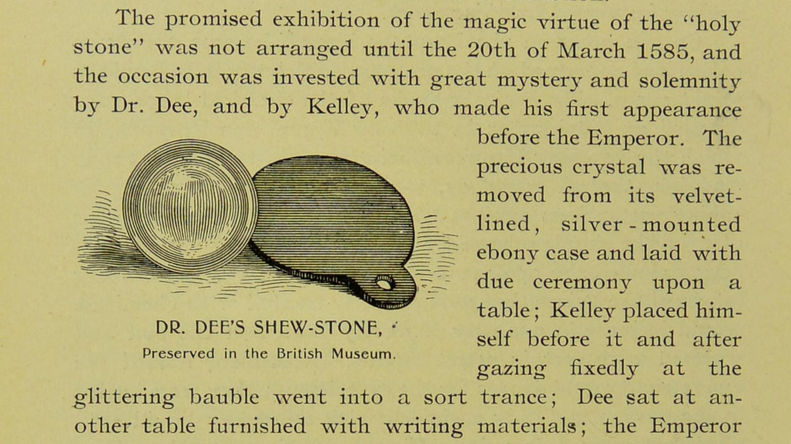

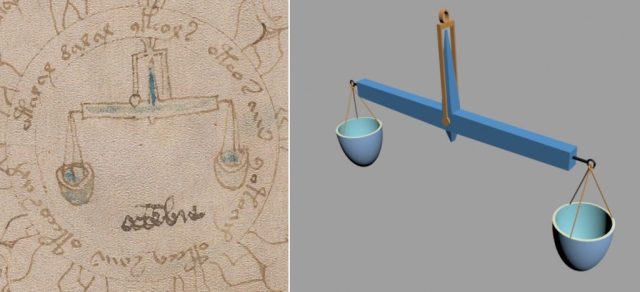

John Dee’s Diary, biographies, & possessions: Many have noted that the Voynich f57v “wheel” may be some sort of “magic circle”, as used by alchemists, physicians, astrologers, and prophets. And John Dee and his activities are related in several places in Follies.

The f57 wheel has several other possible implications, all of which I will not go into here. But one I consider of great interest is the man who is holding up a round object, and seemingly peering at it. That looks to me quite like a “skryer” peering into either a speculum (mirror), or “shew stone” (crystal ball), the practice and devices being heavily tied to John Dee and his notorious sidekick, Edward Kelly.

So is that Edward Kelly, holding up Dee’s shew stone? Well if it is, in this case we actually have the scene illustrated in the Voynich, described in Follies! See below:

OK it does not say he held the shew stone up in the air, as I argue is being done on f57v. Our f57 is “gazing” at something in his hand. I think this is a small point, and that the device and scenario is a very plausible one. And as described further down on the above page 38, Kelley is peering into the stone, while Dee jots down his utterances:

“After a devout invocation to the Almighty in which Dee besought the good will of the angelic host, Kelley, with halting speech and monotonous drawl, began to dictate both the visual and oral mysteries revealed by the spirits in the shew-stone. At first he recited a chaotic mass of absurd rhapsodies in an incomprehensible jargon well calculated to mystify the credulous Emperor…”

Think of this story, related in Follies. Think of Voynich knowing this book by heart, how it was one of his favorite books. And in that context, now think of how many times have we heard the story which is also related right there, in Follies, but about the Voynich Manuscript? That the manuscript was sold to Rudolph on the premise that it held some important and mysterious knowledge? That it was Dee who sold it to him… a part of the provenance sold to a slavish public by no less than Wilfrid himself? And many later theories hung onto this part of the lore, that this was a plot by Dee, and Kelley, to separate the Emperor from his golden Ducats. Well why? Because the work gave people that impression. Because of the story by Wilfrid. And lo, and behold, the actual incident is outlined in the very book I believe was the primer it was modeled after.

Perhaps Charles Singer made the same connection, for similar reasons, as I do, above. In D’Imperio’s “An Elegant Enigma”, the author writes, “Dr. Singer, in a letter to Tiltman (12 November, 1957) expresses the opinion that the origin of the manuscript was somehow related to Rudolph’s court and to John Dee.” She goes on to wonder if Singer was sharing similar ideas to Robert S. Brumbaugh. So I went to my shelf and looked in his book: Yes, he does… and what does he use as a source for his information about John Dee and his associations with Rudolph II? You guessed it… Bolton’s “Follies of Science at the Court of Rudolph II”. He actually refers to it in this context, as a reference for his belief the Voynich is connected to the Court of Rudolph!

I say it is no coincidence that both I and Brumbaugh saw Bolton’s Court in the Voynich, because the Voynich is based on Bolton’s Court.

Selection of Assorted Possible Sources: The below are not all by any means certain, and far from complete. But these some of the many images that I think may have been used as sources for the illustrations in the Voynich. My candidate for forger of this manuscript was, after all, a prolific book dealer, surrounded by masses of sources in his book store stock. He was well traveled, and must have seen many thousands of other books, outside his own, in libraries and museums in England, Italy, France. So it is plausible to me that many of the similar images we see were copied and used in the Voynich.

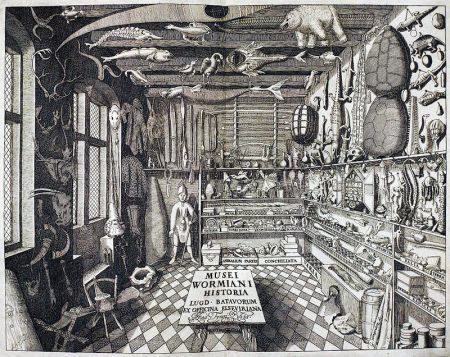

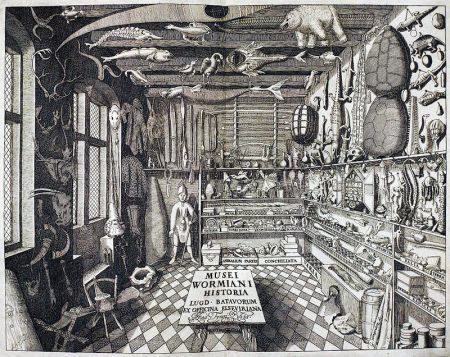

The “Kunstkammer”, or “cabinet of curiosities”. There are many such images. The above is not Rudolph’s, but the general theme of these images, lists and descriptions were, I believe, used as sources for the Voynich. The above one has an armadillo, in fact. The Kunstkammer is discussed in Follies.

Thomas Vaughn, “Lumen de Lumine”: This book (seen here) related various Rosicrucian and Paracelsian themes. Gaspar Schott later copied the image, seen center. The flowers the woman is sitting on, and holding a garland of, are probably roses. The rose and the rose garland are of course symbols of Rosicrucianism. Now look at the Voynich f85v/1 “Garland Girl”. I believe it possible that this illustration is derivative of the image from Vaughn. But it goes further: It has been suggested by others, and I agree, that there ARE Rosicrucian imagery in the Voynich, and also, that this particular page of the manuscript is referencing this. Not only with my supposed rose garland, but by the inclusion of a fleur-de-lis. I also think it possible the man at the top of the center circle is meant to be Martin Luther, who wore a ruby rose ring. For more detail on this, read Is that you, Martin Luther?.

Thomas Vaughn, “Lumen de Lumine”: This book (seen here) related various Rosicrucian and Paracelsian themes. Gaspar Schott later copied the image, seen center. The flowers the woman is sitting on, and holding a garland of, are probably roses. The rose and the rose garland are of course symbols of Rosicrucianism. Now look at the Voynich f85v/1 “Garland Girl”. I believe it possible that this illustration is derivative of the image from Vaughn. But it goes further: It has been suggested by others, and I agree, that there ARE Rosicrucian imagery in the Voynich, and also, that this particular page of the manuscript is referencing this. Not only with my supposed rose garland, but by the inclusion of a fleur-de-lis. I also think it possible the man at the top of the center circle is meant to be Martin Luther, who wore a ruby rose ring. For more detail on this, read Is that you, Martin Luther?.

Deliciæ Physic-Mathematicæ, 1636: This book by Daniel Schwenter (1651 reprint here). My hypothesis does not live nor die by dozens of images that are similar to illustrations in the Voynich. When they have no context in the scope of this theory, there is really no way I could use them to effectively use them as any sort of evidence. But in that light, there are some which, due to some mutual level of peculiarity, I do suspect were in books that surrounded the forger. And the below image, from this 1636 book, is one of those that shares two comparisons with the f79r “floating person” image, specifally the object he/she has their arm wrapped around. If this was the influence for the VMs floating man image, the artist got it wrong: It was meant to be wrapped around the waist, not used outstretched as this one is.

The picture puzzle: Not a specific source, but I feel that the very close similarities between the f27v “root”, and a puzzle piece, cannot be a coincidence. As a root, anyway, it makes no sense. It is a flat slab. I believe this was a little taunt by the forger, realizing that their innate human desire to solve mysteries would see this as a puzzle.

Conclusions: If one wishes to reject one or more of the comparisons above, something must be kept in mind:

These comparisons have context in Bolton: The fact that, through Follies, all these images from the Voynich connect to Bolton’s vision of the Court gives them context, and vastly lowers the possibility that any one of them, let alone all of them, are purely coincidental, pareidolia, or wishful thinking.

These comparisons have context to each other: The similarities between the Voynich cylinders and early optical devices is undeniable, and actually has agreement, even amongst those who believe in the Voynich as real (see below). And people have long thought Voynich images look like cell structures, diatoms, microscopic creatures, and so on. That those two related comparison types are in the same Voynich manuscript defies chance.

These comparisons have agreement: Many people have long thought that many Voynich images seem to be images of microscopic organisms and cells. And many have agreed that my optical device comparisons are very good. In fact on researcher looked into the history of microscopes, as I did. But they could not find such devices in the older time frame that they believed the Voynich was from, and so they discarded the similarities as coincidence. The same thing has happened with the armadillo and other illustrations. But there is often agreement that these comparisons are the best ones, and these things do look like what other suspect, and then are only rejected on the basis of a preconception that the Voynich must be old.

As a forgery from about 1908 to 1910, by Wilfrid Voynich, using The Follies of Science in the Court of Rudolph II as an outline, a Primer, the core starting point, and then collecting many images from many other works, from all times and all geographies, and using them to copy from, or as influences for the Voynich content and style, the Voynich makes perfect sense.

I’m editing this post to add another excellent source, which I believe is a specific one: That is, that one book, or one of several manuscript copies of it, is the actual source of the Voynich’s “crayfish”, “mermaid”, and “bull”, in a 2018 blog post by Koen: https://herculeaf.wordpress.com/2018/09/12/laubers-buch-der-natur-bull-and-crayfish

The background is that for a very long time researchers had wondered at the anatomically incorrect crayfish, or lobster, in the Voynich. It has its legs improperly attached to its tail, rather than the torso of the carapace, where they belong.

And along with the bull and mermaid, one might see, as I do, other stylistic and feature comparisons with other Voynich fish and mammals.

And along with the bull and mermaid, one might see, as I do, other stylistic and feature comparisons with other Voynich fish and mammals.

But as usually happens, my largest interest is in the reactions from those who only except some version of the 1420 Paradigm… that is, at least, that the Voynich must be early 15th century, and genuine. Those comments can be read below Koen’s post, linked above. But what I see in it is a sense of difficulty in explaining the presence of this most probably source of the Voynich crayfish. Did the scribe see a copy of the Buch der Natur? But it is older than the Voynich. Did he/she see a copy of the Buch der Natur? Which one? Or maybe (as is often posited in these difficult situations) there is a “lost manuscript” that both books were copied FROM. And if we find THAT copy, it will explain this.

Of course elephant in the room is not noticed by anyone in these discussions, because even though each time a good comparison is found, similar uncomfortable sentiments whirl around… but the elephant is the fact that it happens in so many cases, disparate cases, that as I pointed out on the Ninja forum discussion about this,

“… looking a the vast corpus of great comparisons all at once, the problem is frankly insurmountable. These 15th century scribes would have had to have been very mobile, which they were not. Or they would have had access to some vast, historically unknown collections, which they did not.

“Or, far more simply, a modern era, 1908 person, with piles of books from all over the world stacked like the walls of a fortress around them, and even had access to trains, and even cars, to rapidly visit the libraries and collections of Europe, therefore having access to all the sources observed in the Voynich.”

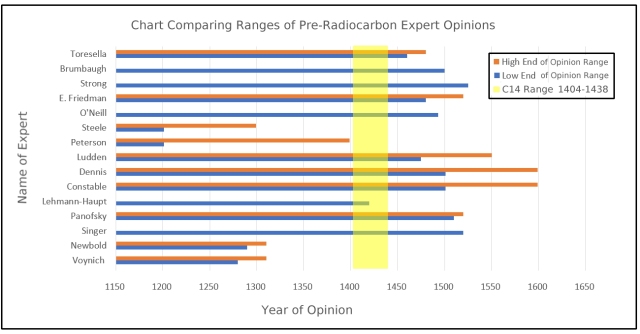

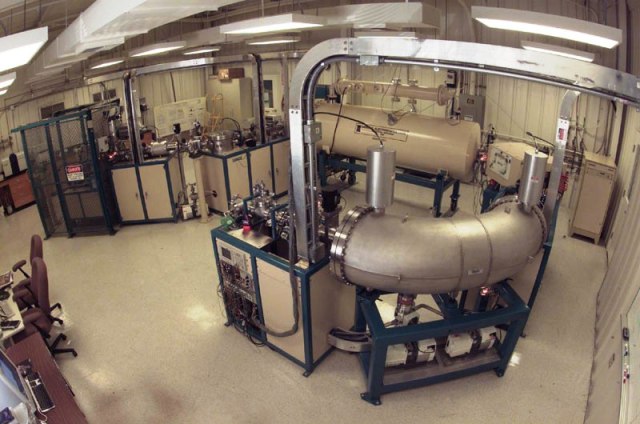

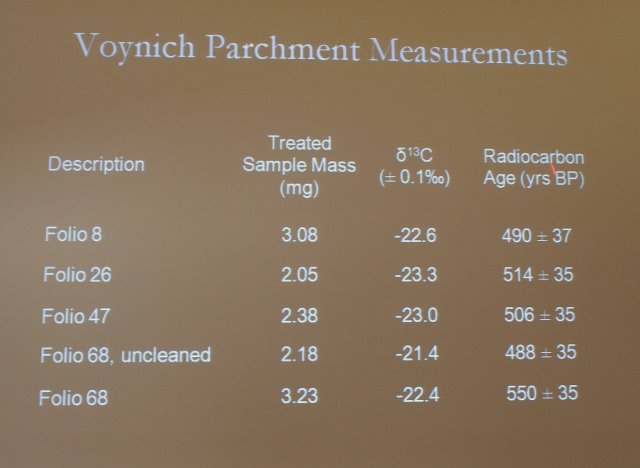

But the same goes for any on the list of experts who are all now said to be wrong. I say, rather than just eliminate their presence, actually explain why they were wrong. Argue with them, don’t simply ignore them. And no, simply saying, “Because C14” does not, should not, suffice. Especially since the dating only tells us when the calf was slaughtered, and not at all when the ink was laid down on their remains. All the content observed, by all these experts, in all their proposed eras, CAN be on that calfskin, if a modern forgery. So explain why they are all wrong, and don’t just tell them to go away.

But the same goes for any on the list of experts who are all now said to be wrong. I say, rather than just eliminate their presence, actually explain why they were wrong. Argue with them, don’t simply ignore them. And no, simply saying, “Because C14” does not, should not, suffice. Especially since the dating only tells us when the calf was slaughtered, and not at all when the ink was laid down on their remains. All the content observed, by all these experts, in all their proposed eras, CAN be on that calfskin, if a modern forgery. So explain why they are all wrong, and don’t just tell them to go away.

One more aspect that ties points in this History documentary to my own work is the idea that Voynich hoped to profit from the forgery. To understand why this is key, I have to relate the fact that for the better part of the last decade my theory was rebutted with the claim that, paraphrasing, “Voynich never tried to sell it, therefore he would not have gone through the trouble of MAKING it”. However, in the Beinecke Libary Voynich archives I found the draft of a letter from Wilfrid Voynich, to Romaine Newbold, offering the man 10% of the first $100,000 realized in a sale of the work, and a further 50% of anything over that, should Newbold’s translation attempts lead to the selling of the work. The point being, he was clearly interested in profiting from it, which countered the previous claims he had no such interest. In the History Documentary, Journalist Amory Sivertson cites the figure “$100,000” as an incentive to forgery.

One more aspect that ties points in this History documentary to my own work is the idea that Voynich hoped to profit from the forgery. To understand why this is key, I have to relate the fact that for the better part of the last decade my theory was rebutted with the claim that, paraphrasing, “Voynich never tried to sell it, therefore he would not have gone through the trouble of MAKING it”. However, in the Beinecke Libary Voynich archives I found the draft of a letter from Wilfrid Voynich, to Romaine Newbold, offering the man 10% of the first $100,000 realized in a sale of the work, and a further 50% of anything over that, should Newbold’s translation attempts lead to the selling of the work. The point being, he was clearly interested in profiting from it, which countered the previous claims he had no such interest. In the History Documentary, Journalist Amory Sivertson cites the figure “$100,000” as an incentive to forgery.

But what I am referring to in this post is an additional and more profound problem with one aspect of the descriptions in the letters.

But what I am referring to in this post is an additional and more profound problem with one aspect of the descriptions in the letters.

Thomas Vaughn, “Lumen de Lumine”: This book (

Thomas Vaughn, “Lumen de Lumine”: This book (

And along with the bull and mermaid, one might see, as I do, other stylistic and feature comparisons with other Voynich fish and mammals.

And along with the bull and mermaid, one might see, as I do, other stylistic and feature comparisons with other Voynich fish and mammals.

Thomas Vaughn, “Lumen de Lumine”: This book (

Thomas Vaughn, “Lumen de Lumine”: This book (

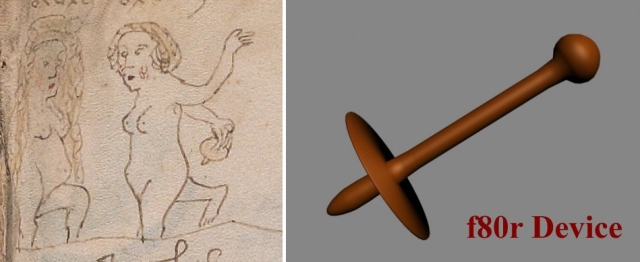

In the past I had wondered if- because of the shape, the positioning, and the assumed medicinal nature of the images on these pages- if this may be related to… ahem… “clysters”, or enema equipment of some sort. Their use for medicinal “colonics” goes back practically

In the past I had wondered if- because of the shape, the positioning, and the assumed medicinal nature of the images on these pages- if this may be related to… ahem… “clysters”, or enema equipment of some sort. Their use for medicinal “colonics” goes back practically

This reminded me of the other object on f80r which I had modeled, as it also seemed to me a possible candidate as a clyster. Note the above item is also held near the rear of the nymph in the second image, and the context of a possible medical interpretation on these pages I already pointed out. It also has the shape of a bladder, which is one form of enema bag. So I commented about my ideas on the Ninja thread, and JKP pointed to the very same thought

This reminded me of the other object on f80r which I had modeled, as it also seemed to me a possible candidate as a clyster. Note the above item is also held near the rear of the nymph in the second image, and the context of a possible medical interpretation on these pages I already pointed out. It also has the shape of a bladder, which is one form of enema bag. So I commented about my ideas on the Ninja thread, and JKP pointed to the very same thought  As JKP noted, there are on both the Voynich and above images a row of dots. The Voynich devices “ruffled” end could be interpreted as the bunched end of a tied off bladder such as this. The image is credited as “MS CLM 337”, which I could not find in color at first. However MichelleL11 pointed me to the color copy. It is in the The Mackinney Collection of Medieval Medical Illustrations, and can be seen at the following link:

As JKP noted, there are on both the Voynich and above images a row of dots. The Voynich devices “ruffled” end could be interpreted as the bunched end of a tied off bladder such as this. The image is credited as “MS CLM 337”, which I could not find in color at first. However MichelleL11 pointed me to the color copy. It is in the The Mackinney Collection of Medieval Medical Illustrations, and can be seen at the following link:

The crop on the above left is the f27v plant root. There have been many attempts at identifying this as an actual plant root, but in my opinion none of them come close to any real root. It me it looks all the world like a puzzle piece. So I modeled it in 3D, and hovered it over a graphic of other modeled pieces. Pieces of this style were only invented in the mid to late 19th century, and from the start they became an iconic representation of mysteries. I have mused on the possibility Wilfrid used this as

The crop on the above left is the f27v plant root. There have been many attempts at identifying this as an actual plant root, but in my opinion none of them come close to any real root. It me it looks all the world like a puzzle piece. So I modeled it in 3D, and hovered it over a graphic of other modeled pieces. Pieces of this style were only invented in the mid to late 19th century, and from the start they became an iconic representation of mysteries. I have mused on the possibility Wilfrid used this as