I am, and have been, accepting of the radiocarbon dating results for the Voynich Manuscript, as released by the University of Arizona. Well, at least as far as I believe it is the best possible current method of testing samples of parchment and vellum for age. But I am a skeptic at heart, and a pragmatist by nature, and to not automatically assume the infallibility of science, or of scientists or their methods of experiment. Not being able to test their methods myself, in many cases, I would have to rely on the hope that their methods are correct and accurate. Better yet, in some cases the scientists test themselves, and their own methods and conclusions… and we would hope that when they do, they can be, well, “scientific” about it. I mean, we must even trust them, in this self-regulation.

In the case of the accuracy and value of the radiocarbon dating of vellum, there is at least one, seminal example. The paper is entitled, “Radiocarbon Dating of Parchment” (Nature, volume 235, January 21, 1972). It is a 1972 paper outlining an experiment meant to apply the current radiocarbon testing methods to parchment and vellum, both to determine if it would be an accurate method of determining the age of manuscripts, and also, as a cross check to the dendrochronology of tree rings… itself used as a check of radiocarbon dating methods. I wanted to see the article to learn more about C14, as I was already pretty much in awe of the ability to date vellum, and wanted to learn more about it. But… I have to say I was somewhat shocked at what I found.

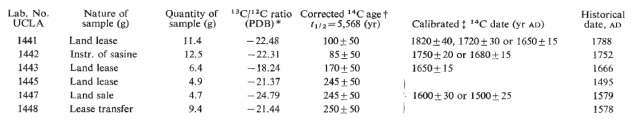

In the test, several samples of vellum, with known dates, were radiocarbon dated. The point was to compare the results to the known dates, to see if the radiocarbon results were accurate, and could be used in the future with any accuracy. Here is the list of the results:

But I think there is a problem with these results. Below I’ve broken them down, and commented on them:

1820 ± 40, 1720 ± 30 or 1650 ± 15 for a 1788 document.

Ok, so they had three wildly varying results… peaks I suppose, or whatever they call them, and chose the closest ones, and ignored the 1650 ± 15 result? Why? Because they knew it was from 1788, so 1650 ± 15 must have been wrong… and, by a minimum of 123 years!

1750 ± 20 or 1680 ± 15 for a 1752 document.

Once again, they used the known date to come to a conclusion: One result was dead on, so they rejected the other… which was a minimum of 57, and a maximum of 72, years off.

1650 ± 15 for a 1666 document.

Very good, they got one right. Well, they got one result, which it happens, was correct. If they had no check, though, they would not have known, of course.

1600 ± 30 or 1500 ± 25 for all three of these: 1495, 1579, 1578.

OK now… this is interesting… they got two results, both the same, for three documents… of two very different eras. That alone is somehow disturbing to me. Why would a 1495 sample give the same results as a 1578 sample? That alone is almost 100 years in discrepancy. And then, they chose to feel it was accurate, but seemingly only by applying the 1600 ± 30 to the latter two documents, and 1500 ± 25 to the 1495 one. How do they know their results reflected the assigned ones? Because they knew the date written on them, that is how. But if they did not have the dates, they would, first of all, had a maximum age difference in the results of 155 years! That is, as old as 1475, to as new as 1630. The 1600 ± 30 result, if applied to the 1495 document, would be an error minumum of 75 years, and a maximum of 135 years.

The procedure they used, discarding results based on known dates, actually showed that the tests alone could not be relied on. They would, in effect, have been clueless with undated samples. In fact, although the testers seem to present the results as though “C14 works for vellum”, they actually have this very telling passage:

It is interesting that the radiocarbon dates after correction and calibration for secular variations correspond to thier known historical ages. But the nature of the calibration curve first developed by Suess sometimes permits age ranges or alternative dates rather than unique dates. Consequently, for samples of unknown age it may be necessary to use independent criteria to narrow the choice.

Italics are mine. But the point is, this whole test of the test could be summed up as follows: “If you don’t know the date of a vellum document, C14 will not give it to you. It could be well over a hundred years off.”

That is bad enough, but there are other problems. In the same article it is stated that vellum “…was used for writing within very short periods of time from manufacture”. But how do they know this? For who is to say that in the case of the 1788 document, the vellum was not made in 1650, as one result showed, and that the 1820 ± 40 result was not the one in error? Maybe the vellum was over a hundred years old. I mean, since vellum had not been accurately dated before, then how do they know how long it sat? There is some serious circular logic happening here… first, they assume that vellum was used soon after manufacture, to validate their use of the known date of the sample, which they then compare to several wildly varying results, then pick the one which closely matches the date written on the document, and conclude the test is accurate! It is an assumption used to chose a result, and then that result is used to back up the assumption. The ouroboros of scientific testing…. the snake eating it’s own tail… creating, the snake again.

Well of course the testing in the case of the Voynich may still be very accurate. For the time being, we really have to assume that. Unfortunately for us, though, the official test results have never been released. We do not know if other results came up during the testing, but were discarded, as they were in the 1972 test. And if there were other results, we do not know why they were discarded. In the above test, we can see what criteria they used… they knew the dates, and threw out the results which did not match their expectations. But in the case of the Voynich, for “expectations”, they would have to use the opinion of scholars. That is, whichever Voynich scholar they relied upon, to make that judgment call.

Hi Rich,

if a C-14 dating result allows 2 or more intervals, the method has no way of knowing / recommending which interval is likely to be the correct one. They are all equally likely.

For a test on a specimen of known date, the only thing that can be verified is, whether or not the date falls inside any of the possible intervals.

If I read your post correctly, this appears to have been the case in each example.

What remains true is that, if you get several intervals, the only way of knowing which one is correct, is by using additional information.

In the case of the Voynich MS, this problem does not exist (for the combined estimate based on the four samples).

Rene

Hello Rene:

“if a C-14 dating result allows 2 or more intervals, the method has no way of knowing / recommending which interval is likely to be the correct one. They are all equally likely.”

Yes, that is how I read this, and something I find somewhat disconcerting.

“In the case of the Voynich MS, this problem does not exist (for the combined estimate based on the four samples).”

What is a “combined estimate”? An average of the results of the samples? I look foward to seeing the raw data, and hope that someday it is released.

Hi,

by the way, is posible VMS is the document written through long time ? As example, oldest part (Zodiac ?) was written about 1420 – 1430, from this time parchement was updated time by time. In this case we have dating of parchement, not of writing time 🙂 And if we can accept not sequential (mixed) assembly of quires or bifolios it is possible, IMHO. Is somewhere proofs against this idea ?

Vytautas

I’ve no reason myself to doubt the Voynich could have been added to over a great period of time, and have seen no “proofs” against it. In fact it has been surmised that the marginalia was added later, and at least one researcher, Nick Pelling, makes a case that the coloring was added after the outlines were drawn. I think he points out the order of pages and quires, along with paint bleed through and transfers, shows this is the case. Search his site, and read his book, it’s in there somewhere.

I am writing a post about other examples of vellum remaining blank for many years, and even, centuries, before being used. In one case, a 16th century vellum book was continuously added to from about 1530, to about 1880, and then was left with many blank pages. So I agree it is a possibility with the Voynich.

Thanks for the comment.

Hi folks,

Never posted here before but the VMS has always been a pet topic for me.

I have always found this work done by Stolfi on the retouching extremely persuasive… http://www.ic.unicamp.br/~stolfi/voynich/04-07-15-retouching/

It really seems like there’s a good chance the VMS as we know it is substantially different from what was originally drawn. In light of the newly established 15th century age for the VMS, does anyone think this sort of thing deserves a 2nd look?

Using newer technology to separate the retouching from the original text (which could possibly be a century older) could reveal a lot more about what it is we’re really looking at…

Like with respect to this site’s Drebbel theory… how much of the detail on the “optics” was added by the retoucher? Could he have mistaken the jars for optics and added the extra detail himself? Finding a better way to separate the images could shed some light on it.

Hi, Danj: Good points of course. Stolfi’s work is excellent.

As for a retoucher making jars look optical, I don’t know… but I do think some of the most important “optical like” features are pre-retouching… such as the recessed tops, the parallel but multiple diameter sides, the possible knurling, the multiple sized collars at the junctures… all features found on early optics. A retoucher may have added the colors, which are also reminiscent of early optics… but in my opinion, even without the added color they are “there” already.

But of course they may simply be jars or other… I’m only addressing this issue, in your comments. Thanks for the feedback… Rich.

Re: Jars / optics. good resemblance to Tibetan Buddhist offering containers for rice.

Hi: There are similarities to various containers seen throughout history, I agree. But still, there are various features on many of the cylinders which do not appear all together on any type of container, candle, soap dispenser, or glassware of any kind, and only on early optical instruments. Of course some cylinders, such as the ones I point out look like Egyptian perfume bottles, do not look optical at all. If you are interested, and have not seen it, check out my post on the subject here:

https://proto57.wordpress.com/2009/06/01/optical-comparisons/

The comparison to some cylinders to early Spanish microscopes I find most compelling.

Also a page of some more optical looking cylinders: http://www.santa-coloma.net/voynich_drebbel/jars.html

And the main site, which has many images of early optical devices, and compares them to the Voynich cylinders:

http://www.santa-coloma.net/voynich_drebbel/voynich.html

So I agree that there are many containers which look somewhat like Voynich cylinders, including your example. But the optical comparisons are too numerous and striking for me to ignore. Thanks for the comments, Rich.

Pingback: Modern Voynich Myths | The Voynich-New Atlantis Theory