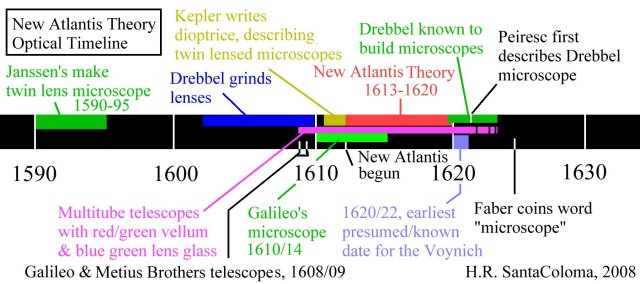

As I wrote in my post, “Optical Comparisons”, the similarity of many of the cylinders in the Voynich Manuscript to optical devices is the starting point of the New Atlantis/Voynich theory. But if the cylinders do represent optics, and if the Voynich is an artifact representing The New Atlantis, then these optical illustrations would have to represent the type of optics from their time, or before… obviously not later. The range of time for the creation of the New Atlantis is unknown, but various experts have placed it from about 1608 to 1623. It was then finalized for print about 1623/24. And the earliest firm evidence for the existence of the Voynich is 1621, if we accept the De Tepencz name as meaning he owned it. So if the cylinders are optical, then they should look like the devices we would expect to see from between 1610 and 1621.

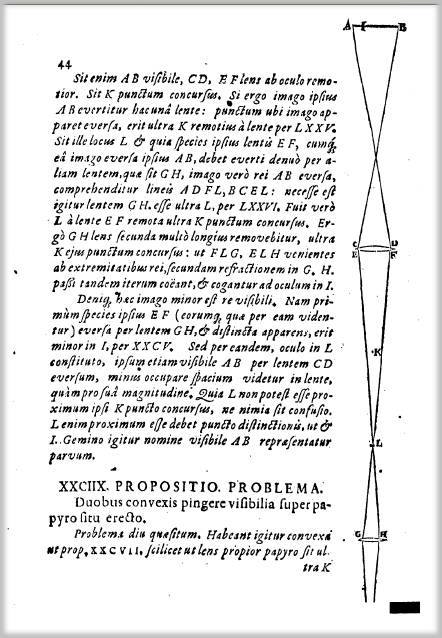

But as for existing examples of microscopes of this time range, none are known to have survived. There is one microscope, the 1595 Janssen device, which pre-dates the range. There is some evidence that Galileo had made a microscope as early as 1610, then one in 1614. And Kepler published Dioptrice, a 1611 book on optics, which contains fine diagrams of optical principles, theories, and devices. Among these is the first description of a twin-convex lens microscope (shown below).

Here is a quote from the Mccord Museum website, “In 1611, Johannes Kepler (1571-1630) suggested the construction of a compound microscope that used convex lenses for both the objective and the eyepiece. The Kepler microscope provided a larger field of view and became the prototype of the modern microscope.”

Of telescopes from this time, we have better examples and illustrations. Of course we are all familiar with Galileo’s 1609 telescope, which tells us what the state of the art optical devices of this time looked like. In this case, the telescope is covered with red and green vellum, and is tooled with gilding along the edges of the segments. These are features which are conceivably represented in the Voynich cylinders… although they are of shorter devices, which I believe could be microscopes. Kepler also owned a telescope about 1610-1611, and it’s design was “based on that of Galileo’s” device. Below is a portion of an accurate modern replica of Galileo’s telescope. The entire telescope is much longer, this is only one end. You can see the replica, made by Jim & Rhoda Morris, and how it was created, at this excellent site.

After the fall of Prague, and the later death of Rudolf in 1612, Drebbel pleaded with James I, to let him come back to London. He professed to be able to build a telescope able to “read a letter at a country mile”. While this is obviously an exaggeration, to make such a claim would be a dangerous gamble if he did not enough experience and knowledge in optics to feel confident of backing it up.

Then, between about 1619 and 1621 in London, Drebbel was producing microscopes for sale. He is credited with the production of the first twin-convex lensed devices. Remembering that this layout was first mentioned in Kepler’s 1611 Dioptrice, and Drebbel shared Rudolf’s court with Kepler, this cannot be a coincidence. Drebbel’s devices must have been based on Kepler’s, either from actual examples, or from the descriptions in Dioptrice. But that is moot to the timing, as it is well established he was making fine microscopes during this time. In fact it was a Drebbel microscope which insprired Faber to coin the term “microscope”… he was marveling at the quality of the lenses, and the clarity of the image of a flea, “the size of a chicken”. He wrote this in 1625, but the instrument was made 1619 to 1621.

The only known drawing of a Drebbel microscope is the one by Issac Beekman, from about 1630. It is probably inaccurately drawn, if the center line is meant to indicate the division between sliding tubes… because the drawing is tapered, and a tapered cylinder would not allow adjustment. And earlier descriptions of Drebbel’s microscopes do not mention such a taper. Here is a CAD illustration I made from Periesc’s 1622 detailed description:

I purposely gave the device generic arcing legs, not reminiscent of Voynich cylinder feet. This, because the shape or design of legs of the extant descriptions are not specified. But interestingly, one description does describe the legs of a Drebbel device as being “shaped like dolphins”. The “delphini” motif has long been popular on legs, often found on Baroque furniture, accessories, and even scientific devices. I argue that the legs on the Voynich cylinders may represent such “dolphin legs”, sometimes head down, sometimes fluke down… both arrangements being known.

At any rate, it has often been suggested that my use of illustrations from after 1620, and even, into the 18th century, to show microscope comparisons to Voynich cylinders, is incorrect and misleading. Also, on a popular blog, the author claims it is re-writing optical history to suggest that microscopes may predate 1620 at all! But even though no known examples of microscopes from between 1610 and 1620 exist, it is clear they were made, they were described, they were explained as early as 1611, and one may exist from as early as 1595. And given the known covering, coloring, decoration, lens glass color (blue and green tint) of the contemporary telescopes, it is not at all unlikely that some of the “lost” microscopes from this time shared these features. This is why I use some later microscopes… they show what a microscope would look like, covered and colored like the known telescopes from “my” time frame. Besides, it is only a few decades from that time frame, to the 1640 to 1675 surviving devices of Divini and others.

But all in all it is clear what the lost microscopes from the period of 1610 to 1620 might have looked like, and that this is quite like what the Voynich cylinders often do look like… whether they are just this, we do not know, one way or the other. H. Rich SantaColoma

Hi Rich,

Drawing visual comparisons with mid-17th century microscopes is a perfectly valid activity (as long as you note the dates) – but you should really add that the overwhelming majority position of optical historians is there is no evidence to support the claim that Janssen built microscopes or telescopes before 1609, let alone 1595 or earlier.

Just so you know! 🙂

Cheers, ….Nick Pelling….

Hi Nick,

The contributions by the Janssens to the development of the telescope and the microscope are long controversial, and certainly open to debate. And the true origins of the actual microscope (I’ll add and image to the post for those interested) sometimes attributed to Janssen is also open to discussion, and may be a mis-identified, later, device.

But it is not settled, and may never be. And I do not ascribe to the belief that a the tally of historians will add or detract from the truth of that history (“overwhelming majority”), any more than the numbers who believe a historical “fact” one way or another will alter the truth. It remains: we do not know for sure. Five historians might be just as right as a thousand whom they disagree with, until and issue is settled by proof.

In any case, the more information which comes to light, the more images and descriptions and devices which are found, it has tended in recent years to indicate that more was achieved in the early years, and not less. The recent discovery of the Kunstkammer telescopes is one example. Your own post, with the image of Jan Brueghel the Elder’s 1617 images of telescopes shows a very modern looking device. It is my sense from all this, and more, that in the coming years that some of the status quo historians will be quite surprised at how much was achieved, and when. I think in fact, that some of the currently unidentified microscopes… often attributed to Divini… should be re-examined, and perhaps date-tested. Golub #124 is one of these.

But in the period which applies to my theories (1610 to 1620), it is obvious that the state of the art of optics was such, and the features, design and decoration actually found, and/or plausible for those devices, are reflected well in many cylinders of the Voynich. I know you prefer various types of glassware over optics for the Voynich cylinders, and I respect that… and of course, you may be correct. I prefer optics, as I feel it is a better match. Thank you for the input… Rich SantaColoma

Hi Rich,

Actually, we now know a fair amount about Zacharias Janssen: and none of it is consistent with a pre-1600 telescope / microscope. This body of evidence (and not merely academic fashion or whim) is the specific reason for the high tally of active optical historians who don’t subscribe to pre-1600 Janssenian telescope / microscope theories.

Cheers, ….Nick Pelling….

Nick: Thank you for your interest, and input… Rich.

You might be interested in the Astrum 2009 exhibition in the Vatican Museums!

Script Enthusiast: Thank you for the tip. I’m in the States, and wouldn’t be able to make it. Hopefully there some images will appear online at some point. Have you seen it? Here is a link to the description:

http://mv.vatican.va/3_EN/pages/z-Info/MV_Info_Eventi.html

Thank you for the comment. Rich.